Eight years ago in August, I cancelled a direct debit mandate for an annual payment of £72 to an organisation in the UK and set in motion a sequence of events that culminated in two criminal prosecutions that revealed the extraordinary lengths our politicians and public institutions will go to conceal their own significant and serious failings, whilst punishing with impunity, those who try to raise concerns about public safety.

Following the report by Sir Robert Francis into the Mid Staffs Scandal, the Government undertook to strengthen the protection offered to whistleblowers after the disclosure of the bullying and intimidation by the Trust against a number of senior medics, including Dr David Drew, who was dismissed by Walsall Manor Hospital after raising concerns about poor standards of care, then lost an employment tribunal for unfair dismissal. Sir Robert was scathing in his criticism of the Trust’s conduct and made twenty individual recommendations to protect NHS employees when they report incidents or circumstances, which puts the public at risk or harm. These recommendations were accepted by Jeremy Hunt, the Health Secretary and in his response to Parliament on 11 February 2015, he said;

“Sir Robert confirmed the need for further change in his report today. He said he heard again and again of horrific stories of people’s lives being destroyed because they tried to do the right thing for patients: people losing their jobs; being financially ruined; brought to the brink of suicide; and family lives being shattered. Eminent and respected clinicians had their reputations maligned. There are stories of fear, bullying, ostracisation, marginalisation as well as psychological and physical harm. There are reports of a culture of “delay, defend and deny” with “prolonged rants” directed at people branded “snitches, troublemakers and backstabbers” and then blacklisted from future employment in the NHS as the system closed ranks.”

Two weeks earlier, in a bleak magistrates court in West London I was experiencing all of that plus bells and whistles – and more, much more was to follow.

There are some subtle differences. First, I’m not an eminent medic but a chiropodist – or a podiatrist, if you prefer. A lowly foot soldier in a relatively minor but remarkably rewarding profession and one that is vital to so many of us as we build up the miles and the years. Second, I don’t work in the NHS, but in private practice and have done so for the last decade. I’m self-employed, or rather I was until two years ago. And third, the organisation that was – and still is – responsible for putting the public at risk from harm is not an NHS Trust but one of the very institutions whose principal statutory responsibility is safeguarding – the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), the second largest health regulator in the UK, which was established by the Blair Government in 2003 as part of a raft of reforms to healthcare regulation in the wake of Shipman, Alder Hey and Bristol.

Up until then, I had been a state-registered podiatrist after qualifying from Edinburgh in 1983. I’ve practised throughout the UK in the NHS and in private practice and count myself extremely fortunate in my choice of vocation – as much for the individual patients who have enhanced my life enormously on a personal level as for the complex and challenging conditions we routinely encounter on a day-to-day basis, that very much keeps the professional interest alive. Even after three decades.

I see patients from all age groups; children with their verruca and ingrown toenails, professional footballers and athletes, high-risk diabetics and ladies with improbable shoes. Many of my patients are elderly, frail and extremely vulnerable, especially when confusion and isolation are attendant companions -and are often susceptible to risk and harm in our world today. Whenever possible, and especially with their health and social care, we must try to prevent that risk and harm from occurring in the first place.

In 2003, I was elected as a member of Council for my professional body, the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists – which is our equivalent of the BMA – and for two years I would travel down to London for a day at a time to sit through some mind-numbingly and tedious committee meeting before taking away a vast bundle of papers to try and make sense of in my spare time. That adventure lasted twenty-three months longer than it should have, but one of the matters I had responsibility for – in a limited capacity – was the regulatory regime that was being introduced by the newly formed Health Professions Council (they added “Care” when the regulator adopted responsibility for Social Workers in England and Wales in 2012).

I had little or no experience of regulation or professional organisations until then. Coming from a purely clinical background, I’ve avoided management and committees whenever possible, but after two decades in the profession, I thought I should try and give something back – although what and whether it might be of any value, I had no idea. In hindsight, it might not have been the wisest decision in my life.

One of the ways a health regulator “protects the public” is by maintaining a register of professionals that subscribe to strict standards of care, competence and conduct. When a complaint or concern is raised against a registrant professional, the regulator will investigate and hold a fitness to practice hearing if they consider the individual has a case to answer. If proven allegations against the registrant are of sufficient gravity that they place the public at risk, then the regulator may strike that individual off the register. The HCPC claim:

“Our fitness to practise process is designed to protect the public from those who are not fit to practise. If a registrant’s fitness to practise is ‘impaired’, it means that there are concerns about their ability to practise safely and effectively. This may mean that they should not practice at all or that they should be limited in what they are allowed to do. We will take appropriate action to make this happen.”

What happens is this.

When someone is removed from the register, they cannot use the title of that profession anymore. In the NHS where employment is conditional on a valid registration, an individual who has been struck-off will lose their job and in that respect, the patients in the NHS Trust where that individual worked will be less exposed to harm. In theory, at least.

The problem arises, not in the NHS, but in the rapidly expanding private sector, where clinicians, like myself are often self-employed or work for companies where valid registration with the statutory regulator is not a condition of employment. In these circumstances, someone who has been struck-off following a fitness to practice hearing can perfectly legally practice in the private sector by simply using a different unregulated title. In other words, the HCPC’s claim that they can prevent a dangerous registrant from practising, is untrue.

In the world of feet, chiropodist and podiatrist are titles regulated and protected by the HCPC – but there are a variety of others such as Foot Health Professional, Gait Specialist and Podologist that are commonly used by those who practice outside regulation, without registration. To the casual observer, this may appear quite strange, but for professions with an established private sector presence, it has always been thus.

One of the unforeseen consequences of health regulation in the UK is a two-tier system of care in many health professions. In the regulated sector there is an expectation that your care will be provided by someone of good character, with the requisite training and qualifications and who adheres to all the relevant standards of proficiency and conduct at all times.

But in the unregulated sector, there are no such safeguards or scrutiny and although you may receive satisfactory treatment and good care, you might also find yourself being treated by someone with no qualifications or training whatsoever. Or indeed someone that has been struck-off the statutory register.

One of the features of the HCPC – and indeed all the health regulators today – is their online presence, which includes their Fitness to Practice Hearings. For the first time, the public has access to not only allegations and complaints against registrants, but all the evidence and subsequent outcomes. It can make for an illuminating if occasionally disturbing read.

Towards the end of my two-year stint with the Society, I became aware of two pending FtP cases involving colleagues that alleged sexually motivated conduct of the utmost gravity. Both cases were subsequently proved and the individuals were struck-off, but some time later I was contacted by an officer from the Serious Sexual Crime Unit in Manchester who informed me that the individual concerned was still in practice and had been since the police reported the matter to the HCPC during their investigation.

The regulator carried out its statutory duty, investigated the complaint and held a hearing, which concluded the public was at serious risk and duly sanctioned a striking-off order, but as so often in these cases, the registrant was not present and did not contest the allegations, as they are not compelled to do. Usually, they are too busy working – under a different, but perfectly legal guise.

Over the next two years, however, it became apparent that this was a developing problem and not one restricted to just my own profession. The HCPC regulates sixteen health professions in total, many of whom, like podiatry, have a substantial private sector presence. In addition, the legislation that governs the HCPC is analogous with that of the Nursing and Midwifery Council – the largest health regulator in the UK – and after speaking to colleagues in the nursing profession, it was apparent that many in that profession who had been subject to FtP proceedings and struck-off, were still working in the private care sector in a healthcare/nursing role. In some cases with proven accusations of neglect and elderly abuse.

I first raised this concern with Gordon Brown, my constituency MP in Scotland during a meeting about NHS chiropody provision. He suggested that I raise this matter with the Chief Executive and Registrar of the HCPC and secure a response before he would consider it further.

A few months later, I attended what was described as a “Listening Event” – chaired by the Registrar, Mr Marc Seale, in Preston and during the Q&A session I voiced my concern about the risk posed by those registrants who had been struck-off but were still practising in the private sector using an unregulated title.

He replied that, as I “was well aware, the HPC was governed by the legislation handed down to it by Parliament.” There was no offer of a supplementary question.

The previous year in 2006, I had just started a private practice in a small complimentary health clinic in Lytham St Annes near Blackpool. It had been a busy year. I am a recognised provider and consultant with the Premier League Health Scheme and with Blackpool’s rising ambitions, there was a steady stream of players most weeks in addition to a rapidly expanding caseload from the area’s large retirement community. It was a couple of weeks before I found time to sit down and write the first letter to the Registrar which simply asked if he would be kind enough to answer the question I posed to him at the meeting. I didn’t receive an answer. I wrote again with the same outcome and eventually, in August 2008, I telephoned the HCPC and spoke to a case manager.

It was a friendly conversation and he appreciated my concerns and understood them perfectly, but he also reiterated that the organisation had to function under the constraints of the existing legislation and only Parliament could amend it. I asked if the Registrar would acknowledge my concerns, particularly the risk to the public in the private sector following a striking-off order, but was informed that was all that the Registrar had to say on the matter.

Without, I have to say, a great deal of consideration I wrote a short, final letter to the Registrar. That month, my annual registration fee was due to be collected by direct debit. It was my twenty-fifth year in practice as a registered podiatrist but with little hesitation, I telephoned my bank and cancelled the mandate then sat down and composed my letter. I advised the Registrar that I was withholding my fee until he replied to my correspondence. Furthermore, I would still practice calling myself a podiatrist. Two weeks later, I received my first “cease and desist” letter informing me that I was breaking the law if I used a “protected title” without registration and may be subject to a criminal prosecution with a fine of up to £5,000.

I’ve never broken the law before – although that is not to say I haven’t had a few interesting adventures – and whilst my personal life has been dramatically chaotic at times, I’ve always taken a great deal of pride and care in my professional life, not least because of the trust that is so vital in the relationship with our patients. But I really didn’t give it a great deal of thought at the time.

I had no idea why the Registrar would refuse to reply other than to say we must all do what we are told, but I’m afraid I don’t respect that kind of approach. I thought it a legitimate concern – after all, his organisation quantifies the risk in the first place. The only problem is that because of the legislation, the risk is simply moved elsewhere, out of sight, away from further scrutiny. Unless, of course, you are an unsuspecting member of the public.

If I hoped that being stubborn might provoke a change of heart, I was badly mistaken. Three months pass without any contact, then a second “cease and desist” letter appears in time for Christmas and I realised then that any expectation for a satisfactory conclusion was diminishing rapidly.

It still didn’t trouble me greatly. I couldn’t imagine any circumstance where a regulator that I had been affiliated to for twenty-five years would launch criminal proceedings against me for withholding a registration fee in protest for the aforesaid reasons.

It is worth remembering that these events took place fours years before the Francis Inquiry was published and although the culture of provocation and intimidation was well established and prevalent in the NHS and the Institutions by then, I had little personal experience of it. That would soon change dramatically.

I had discussed the situation with my colleagues at the clinic where I worked, including the owner, an osteopath and all the secretarial staff and they were in full agreement with my decision. Over the coming months the clinic changed my stationery and business cards and removed all references to the HCPC and I started incorporating the story of my criminal behavior into the daily dialogue with my patients. Those that had the capacity to understand what I was wittering-on about were always fully supportive and didn’t mind one bit if I was registered or not. As far as the public were concerned, it made no difference.

However, some patients have health insurance policies that reimburse some of the costs of private care from chiropodists and other health disciplines and most of these companies stipulate that care is provided from registered professionals. I knew this. It had been discussed and promoted by the Society’s Council when I had been a member and something I had supported enthusiastically, but now that I had ceased registration, some patients would be unable to claim any reimbursement for my fees.

I clearly had an obligation to ensure they were aware they couldn’t claim and established a register of all those affected. From a caseload approaching 2,000 patients, sixty-three individuals held policies that could no longer be used unless they changed practitioner. No one did.

Over the next two years there was intermittent contact with various case managers at the HCPC usually following receipt of another “cease and desist” letter. One email correspondence also concerned the presence of “HPC Registered” underneath a photograph of me on the clinic website that their IT consultant had omitted to remove, when first instructed. It had gone unnoticed for two years but had been seen by someone at the HCPC and I was asked to remove it – which was duly done by the clinic’s owner. Our conversations were, without exception, polite, professional and friendly, as I would have expected. Like most colleagues, I thought we were on the same side. In 2010, a case manager asked if I would re-register if he could secure a reply from the Chief Executive and I said that I would. A fortnight later, I received a letter from the same case manager thanking me for my concerns before adding that “the HCPC had to function within the constraints of the legislation handed down to it by Parliament…”

Needless to say, I didn’t re-register.

Three years later on the 4th April 2013 and in much different circumstances, I received a summons to appear at Westminster Magistrates Court charged with using a Protected Title (chiropodist/podiatrist) without being registered with the HCPC – and a nightmare that I could not possibly have foreseen, began in earnest.

I am not one for protests normally. Experience has shown that in the main, they are an ineffective way of securing real change, especially with Government policy. Consider the anti-war demonstrations before the Iraq conflict, for example – and more recently, the Junior Doctors industrial action in the NHS. If anything, ‘protest’ leads to entrenchment and polarised opinion and this usually inhibits any resolution of any contested issues at hand. I have always taken the view that voicing concerns should be a starting point for meaningful discussion – and with an underlying principle of co-operation rather than conflict, one can usually make progress. Open, honest and transparent communication is the key, however it has to be acknowledged that is not always possible, especially with national security issues like the war in Iraq. There are clearly circumstances when Government and its institutions cannot provide full disclosure and candour, however refusing to acknowledge and respond to a valid and genuine concern for public safety created by a weakness in health regulation, wasn’t one that I had envisaged. Nor was the prospect of a criminal prosecution, despite the threat of one each time a “cease and desist” letter arrived informing me that I was breaking the law by practising under a “protected title” without valid registration. In hindsight, I was terribly naïve.

I had a number of difficulties that I had not considered or even envisaged. I worked in private practice. Like most of my colleagues, I was self-employed – a sole trader in every sense – and as such, we have none of the ‘protection’ that is offered to employees of the NHS when they raise concerns. The so-called Whistleblower’s Charter.

Also, it was a regulator, not the NHS that was creating the risk – an organisation whose principal responsibility is to “protect the public”, not create circumstances that potentially puts them in harm’s way. The danger to the public was quite clear in my mind and I could not fathom why the Chief Executive would not even acknowledge there was a problem never mind discussing a solution. It would be some time before I discovered the reason.

The summons included the charges, witness statements and file notes from the HCPC, a copy of the relevant legislation and an evidence bundle that was several inches thick. I was to appear on 22 May 2013 at Westminster Magistrates Court for an initial hearing and to make a plea of guilty or not guilty. During the previous three years I had published several articles online about the dispute, primarily to keep colleagues in the profession informed about any developments – and also to keep a publicly available record explaining the reasons why I was no longer registered. A number of these articles were also included in the papers and in all of them I had stated that I was breaking the law by practising as a podiatrist without being registered. I had admitted my guilt numerous times over the previous five years – and although I had not envisaged ever being in a position of answering to these charges in court – I had deliberately flouted the legislation by withholding my fees and on that basis I would have to plead guilty. However, when I read all the supporting documents in the evidence bundle, I changed my mind.

It had been almost five years since I ceased registration when the summons appeared and it was not without incident elsewhere. The year before I was charged, the atmosphere in the clinic where I worked deteriorated rapidly when the owner encountered serious financial difficulties. Over the course of a difficult and acrimonious year, all the staff and clinicians left and found new premises leaving behind much animosity.

Contained within the evidence bundle was email correspondence from the clinic owner’s wife complaining to the regulator that I had been practising using a “protected title” without current registration. Attached to this complaint were copy invoices and letters taken from my patient files that stated I was HCPC Registered and included my registration number. The documents post-dated my de-registration, but when I checked them against the originals in my patient notes, references to the HCPC and my registration number were absent. In addition to the fabricated file notes, there were other documents that I had not seen before, including an insurance claim for a minor surgical procedure but no details of the patient or any reference number.

Whilst I had resigned myself to pleading guilty, I wasn’t prepared to have erroneous information retained in the summons as a matter of public record. I sought legal advice from a local solicitor who advised that I take all the original documents to court and seek agreement from the HCPC to remove the complaint and all other contested documents from the evidence before making a plea.

We also discussed legal representation. The cost of instructing Counsel and preparing a defence for a London hearing was prohibitively expensive – and as I was intending to plead guilty once agreement had been reached on the evidence, I decided against it. Legal aid was not an option.

I have often wondered whether this was a mistake, but as I thought I had clearly committed the offence and that the only reason I had for doing so was not a valid defence in law, I had no intention of wasting court time or incurring needless costs to appoint a barrister to plead guilty in any event. With the benefit of hindsight, it would not have made much difference anyway.

Had I any worries about the proceedings, I was immediately put at ease by the prosecuting barrister and solicitor who were courteous, professional and very understanding. I was told that this was a “very reluctant” prosecution and they had much sympathy for my concerns about the regulation. However, the only consideration was whether I had broken the law and how I intended to plead. I explained why I was unhappy about some of the evidence and gave them copies of the original paperwork and two witness statements from the secretaries at the clinic where I had worked. After reviewing these documents, they agreed this evidence was unreliable and should not be put in front of the court. I was then asked how I would plead if the contested documents were removed from the evidence and I confirmed I would plead guilty to the charge of using a protected title without valid registration.

Two weeks later, agreement was reached to remove the offending evidence and the court set a date for 11 November 2013 for sentencing at the City of London Magistrates. I was to prepare a Mitigation Statement that I could read out in court before sentence was passed and a copy was sent to the solicitors in early September.

I had no idea what to expect. At 2pm on Armistice Day, I walked into the court and was met again by the same agents for the HCPC. The barrister explained that the charge would be read out and I would be asked to make a plea. Thereafter she would present a case summary before I gave my statement in mitigation of sentencing. Finally, I was handed a hand-written sheet of the prosecution costs and was told that they may ask the court for some of the costs to be awarded along with any fine that might be imposed.

I had assumed the prosecuting barrister would tell the court that whilst I had used a protected title without being registered, I had done so for good reason; but they were reluctantly seeking a conviction to uphold the law. My assumptions were badly misplaced.

I was characterized as being a mischievous individual intent on pursuing a relentless campaign against the HCPC for reasons unknown; that I had lapsed my registration following a dispute about the legislation and that I had deliberately misled and deceived patients, colleagues and the public into believing I was registered by signing myself variously on letters, invoices and other documents as a HCPC Registered Chiropodist/Podiatrist. The motive for acting dishonestly was to ensure I maintained an income to fund my ill-conceived campaign against the regulatory regime.

From that moment, life has taken a rather different direction to what I am accustomed to.

I was stunned with what I heard – as were two colleagues who had come along to court to give some support. I could barely think straight as I rose to read my statement – and in any event I was stopped by the magistrate after a few sentences and told I didn’t need to read any more as they had been given a copy before the hearing. I was fined £270 and told to pay the HCPC’s costs of just over £5,000.

Four days later, the HCPC issued a press release:

The Court found Mark Russell guilty of an offence with intent to deceive under Article 39 of the Health and Social Work Professions Order 2001. He was fined £270 plus a victim surcharge of £27 and was ordered to pay the HCPC’s legal costs. Individuals cannot practise in the UK using one of our protected titles unless they are registered with the HCPC. It is a criminal offence for someone to claim that they are registered with us when they are not, or to use a protected title that they are not entitled to use. We will prosecute people who commit these crimes, as we have done with Mr Russell.

I was still in a state of shock from the court proceedings a few days previously, but that was nothing to the feelings of despair and anger I felt when I read this statement. When I contacted the HCPC’s solicitor to ask why they had written “an intent to deceive”, I was told, curtly, that was the offence that I had pled guilty to and the regulator was entirely correct to publicise it as such.

Two days later, the HCPC contacted my local newspaper in Blackpool and asked if they would publish the press release, but thankfully the reporter contacted me first and I was able to explain the reasons why I had ceased registration and a balanced article was published early in January 2014.

I had no idea what to do. I could not comprehend that a prosecutor would present evidence in court that she knew to be wholly wrong and misleading and to refer from documents that were removed from the case by agreement, as they were “unreliable”. I was only concerned that this evidence was removed from the case as it suggested I had been dishonest with a former business colleague – and that was untrue. As far as I was concerned, I had committed an offence, but I had done so openly and honestly and had never deceived anyone.

I was utterly despondent over Christmas and New Year. I may be terribly naïve at times, but I am not stupid and realised with not a little embarrassment that I had been completely duped by the prosecution and was baffled why they would try and depict me in the way that they did. Over the festive period, I researched what grounds of appeal I might have, but as I had already pled guilty, my options were limited, if any at all.

After writing to the clerk at Westminster Magistrates Court and explaining my predicament, I was advised to submit an application to the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey for consideration. Later that week, I was contacted by a local solicitor who had read of my conviction in the newspaper and he suggested that I had grounds for a successful appeal as I could not possibly have committed the offence in the first place unless I had an “intent to deceive”. He explained that although the legislation provides three circumstances where an individual can be guilty of misusing a title, they are all conditional of an accompanying intent to deceive. In his opinion, if I was qualified in podiatry, did not claim to be registered when I wasn’t and did not deceive anyone into believing I was registered, then it was perfectly legal for me to call myself a podiatrist without breaking the law.

I found this difficult to believe, as this was contrary to everything I had been told by the regulator – and my professional body, the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists. However, on close reading of the legislation there is indeed a qualifying sentence before the offences are described which states:

Article 39.1: A person commits an offence, if with intent to deceive, either expressly or by implication –

(a) he falsely represents himself to be registered in the register, or a particular part of it or to be the subject of any entry in the register;

(b) he uses a title referred to in article 6(2) to which he is not entitled;

(c) he falsely represents himself to possess qualifications in a relevant profession.

I was charged under section (b) and as I am entitled to call myself a podiatrist by virtue of my qualification, the essential ingredient of the offence in my case was the “intent to deceive”. Without any dishonesty or deception, I could not have committed the offence.

This took a little time to digest. I contacted several colleagues who were closely involved with the discussions with Government during and after the consultation period when the HCPC was established and without exception, they too were ignorant of the necessity of a qualifying criterion for an offence to be committed.

At no time were we informed of the significance an “intent to deceive” – we were led to believe that the crime was one of strict liability – that using a title without registration was an offence on its own. At the time, I could not comprehend why.

An application to vacate my guilty plea was made at the Old Bailey on 26 February 2014. This time, I was represented by my solicitor and Junior Counsel and was presided over by HH Judge Pontius. During the evidence, the barrister for the HCPC agreed with the Judge that the defence submission that specified an intent to deceive was an essential part of the offence, but argued that if I had wanted to ensure compliance with the legislation, I should have prefixed the title of podiatrist with “unregistered” or “formerly HCPC registered” so the public would be in no doubt of my registration status.

No one had told me I could do that. During evidence, I explained this to the Judge when he asked me why I had pled guilty at the Magistrates. He enquired whether the prosecution had told to me that “an intent to deceive” was to be omitted from the charge during any discussions, but I could not recall it even being mentioned; certainly the significance as part of the offence was never explained.

The Judge granted our application and procedurally, the case was sent back to the Magistrates Court and the prosecuting barrister was asked to dismiss herself from any further proceedings. It was a remarkable day, not least as the hearing was held in all the splendor of the Old Bailey on the same day as the murderers of Lee Rigby were being sentenced and Justice Coulson was hearing evidence in the Brooks/Coulson phone-hacking trial. It seemed surreal that this insignificant matter had progressed to this stage. It was also quite terrifying.

I had stopped practice at Christmas after the HCPC issued their press release. I had rented a room in a family run clinic adjacent to a pharmacy with a radiographer. They were incredibly supportive over what had been a difficult year, but I felt I could not carry on in practice whilst the regulator was promoting a conviction, which is essentially one of dishonesty. After the Old Bailey hearing, I thought the HCPC would issue an apology and retract the press release, but a month later they simply amended the notice to confirm my application at the Old Bailey was successful and the case had been sent back to the Magistrates and offered no further comment.

I assumed that would be the end of the matter – my prosecution, that is. But I was also aware that the HCPC were in a difficult position too. It appeared that the regulator has deliberately concealed the important relevance of an “intent to deceive” since it was established in 2003. None of the professional bodies or registrants would have been aware that it is possible to use a “protected” title without registration in some circumstances – and whilst it was not the subject of my own concerns, the implication of the actual legislative position is that a registrant who has been struck-off is not only able to remain in practice – and at risk to the public – they can also practice under a “protected” title provided they make it clear they are no longer registered. If anything, my concerns were even more justified.

Two months pass and there is no contact from the HCPC but during May 2014 I am notified that there is to be a second prosecution and a hearing is set for the City of London Magistrates Court for 17th September.

The HCPC appointed a leading QC to prosecute; I have also appointed a barrister and this time have entered a “not guilty” plea. The case was listed for one-day, however the prosecution case took until 3.40pm and the District Judge adjourned the matter until 29th January the following year. Once again I am characterized as being a mischievous individual, but this time the court was told that I am also responsible for a relentless political campaign against the regulatory system and the HCPC, which the latter was forced to defend through a criminal prosecution – at great expense to my colleagues whose fees were funding the prosecution. I’m sure the forty or so podiatrists who were in the public gallery were thinking the same as I was at the time; if the Registrar had only replied to my initial concerns, there wouldn’t have been a prosecution in the first place.

I’d not practiced for nine months and had no income and what little savings I had at the start of the year, had almost gone. I wasn’t sure how I was going to manage for another four months. I already borrowed some money from my family to help meet the legal costs for the September hearing and I would have to find the same again for the final hearing in the New Year, although how and from where, I wasn’t sure.

The case resumed in Hammersmith Magistrates Court in January. I was very confident after the first hearing; much of the legal argument concerned the legislation and once again it was admitted that “an intent to deceive” was an essential element of the offence. As I certainly never intended to deceive or mislead anyone, I couldn’t see how I could possibly be guilty.

Another admission was that there is no such thing as “protected” titles in the legislation as only “designated” titles appear in the Order. One of the functions of the HCPC is to “protect” the titles, but their ability to do so is impaired by the “intent to deceive” element. If an individual can legally use a designated title without registration, then it is misleading, at best, to claim the titles are “protected” in law – as they had done since 2003. Another layer was being peeled away.

Unfortunately, I was found guilty. The Judge decided that a sentence I had written on my website that read “Hello, I’m Mark Russell and I am a podiatrist..” constituted a breach of the legislation on the basis that a member of the public reading that sentence might infer that I was a “registered” podiatrist if they had knowledge that podiatrists were subject to registration with the HCPC, therefore a deception could occur. I was fined £200 and ordered to pay £1,000 in costs.

The sentence appeared on my website – a blog that was set-up solely as an online record of the case with the HCPC. Anyone visiting the website could be in no doubt that I ceased registration – and why. In his summing up, the prosecuting QC once again averred that I could and should have prefixed the title with “unregistered” or something similar to ensure there was no prospect that anyone might be misled. Which is quite true. But I hadn’t been told that.

I wasn’t prepared to let the matter rest. I hadn’t deceived anyone and was completely open and honest about my protest with the HCPC since I ceased registration, yet I had a criminal conviction, which specified just that. It is over a year since a stopped my full-time practice and I am already heavily indebted.

The conviction was appealed and an application made to transfer the case to Lancashire. Each hearing in London had incurred costs of over £4,000 and I wasn’t sure if I would recover any of these even in the event of an acquittal. All I could hope for was a quick, successful appeal so I could get back to some sort of normality.

The HCPC opposed the application for a change of venue to Lancashire and another hearing was set for September in Preston to resolve this and eventually, a two-day Crown Court Appeal hearing was scheduled for 1st and 2nd October 2015 in Lancaster Castle. The nightmare was about to take another twist.

I had realised the previous summer after I received notification that there was to be a second prosecution that I was in the middle of something I could not have possibly foreseen. What started as a stubborn protest over a unacknowledged concern about medical regulation, had developed into a criminal trial of Kafkaesque proportions, which I had no control over. I most certainly had not deceived anyone, yet I had been publicly accused of being dishonest by a prosecuting authority who had deliberately concealed the true nature of the offence I was charged with since they had been formed in 2003.

I published an article that summer in our professional Journal about the case and was immediately inundated with calls and messages from colleagues throughout the UK whose understanding of the legislation was consistent with my own and who were similarly unaware of the “intent to deceive” requirement. A few weeks after the article was published, the Nursing and Midwifery Council issued a notice of guidance on their website regarding titles. It read:

The NMC’s position regarding the use of qualifications after registration has lapsed is governed by article 44 of the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001:

“44 – (1) A person commits an offence if, with intent to deceive (whether expressly or by implication):

(a) he falsely represents himself to be registered in the register, or a particular part of it or to be the subject of any entry in the register

(b) he uses a title referred to in article 6(2) to which he is not entitle

A person guilty of an offence under this article shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale.”

Article 6(2) states:

“Each part shall have a designated title indicative of different qualifications and different kinds of education or training and a registrant is entitled to use the title corresponding to the part of the register in which he is registered.”

It is important, therefore, for nurses and midwives to distinguish between their qualifications and registration status. Those who allow their registration to lapse can still refer to the fact that they are a qualified nurse, midwife or specialist community public health nurse but must not give the impression that they have a current registration.

As the NMC legislation is analogous with that which governs the HCPC, I thought, for some reason, that might be an end to the matter, but as the start of the second prosecution drew near, I realised that was a forlorn hope. What was equally concerning was the inclusion of the contested evidence from the first case – the malicious complaints solicited by the osteopath and the fraudulent documents.

I was astonished after the Old Bailey hearing and angry enough to lodge conduct complaints with the General Osteopathic Council and the Bar Standards Board; the former against the osteopath whose malicious conduct had provided the “evidence” of dishonesty which the HCPC considered sufficient to fulfill the intent to deceive requirement. The Osteopathy regulator investigated the complaint and took witness statements from the staff at the clinic where we worked and concluded that there was a case to answer and scheduled a FtP hearing for October 2014 – a month after my second prosecution was due to be heard.

The other complaint concerned the barrister from the first prosecution. With hindsight, I could understand the reluctance to explain the necessity of proving an “intent to deceive” as I would have realised that was not consistent with her client’s – the HCPC’s – publicly declared position. I thought it was sharp practice and would have thought that someone in that position would have been completely forthright about the charges I was actually facing. Following the completely unexpected character assassination at the sentencing hearing and the admission at the Old Bailey that I could have used “unregistered” to evade prosecution, I realised to my great embarrassment that I had been completely hoodwinked from the outset, but on 11 August 2014 the Bar Standards Board informed me that there was insufficient evidence to take the matter to a formal investigation.

In late September, three weeks after the second prosecution started in London, I received a letter informing me that the Osteopath’s hearing had been postponed and a new date would be set in the New Year. The week following my conviction at Hammersmith Magistrates Court in January 2015, another letter notified me that following legal advice, the Osteopathy regulator has decided to abandon the conduct hearing altogether on the grounds that my conviction rendered me an unreliable witness and they would be unable to prove their case. When I received the formal notice of discharge, I was shocked to discover that the legal assessor advising the GOsC is also a legal assessor for the HCPC.

Over the course of last summer and in the months leading up to the appeal in Lancaster I became completely overwhelmed by these events. The last two years had been spent in some tortuous limbo punctuated by single days of intense activity in court – followed thereafter by a period of reflection and redefining perspective. The whole business seemed mad; I was on the edge of losing my career, reputation, income and savings and much more for simply raising a concern about public safety – and in doing so, I had incurred the wrath of just about every authority imaginable. There seemed no way of stopping it as I was plunged into a world where common sense had withered and died.

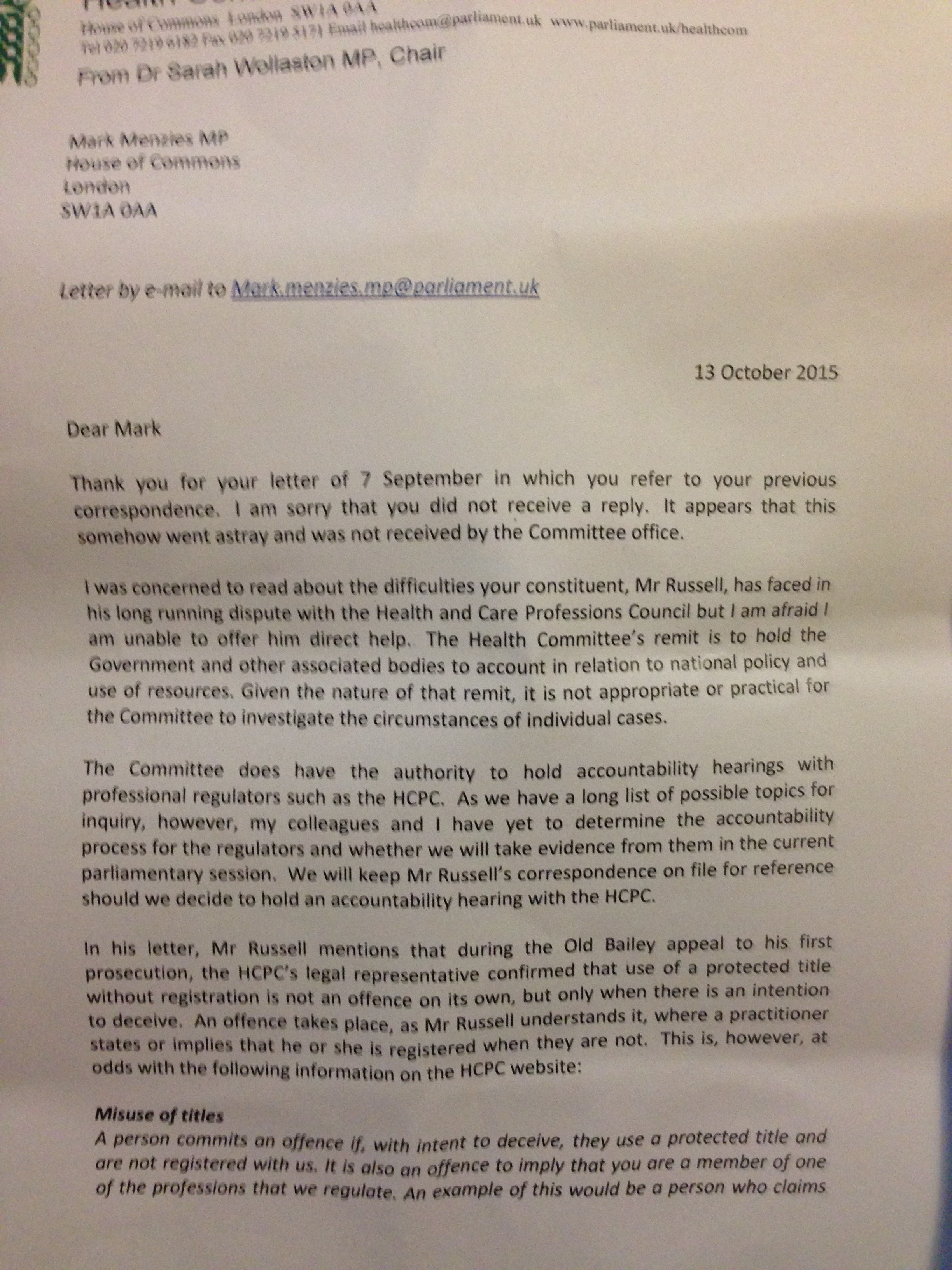

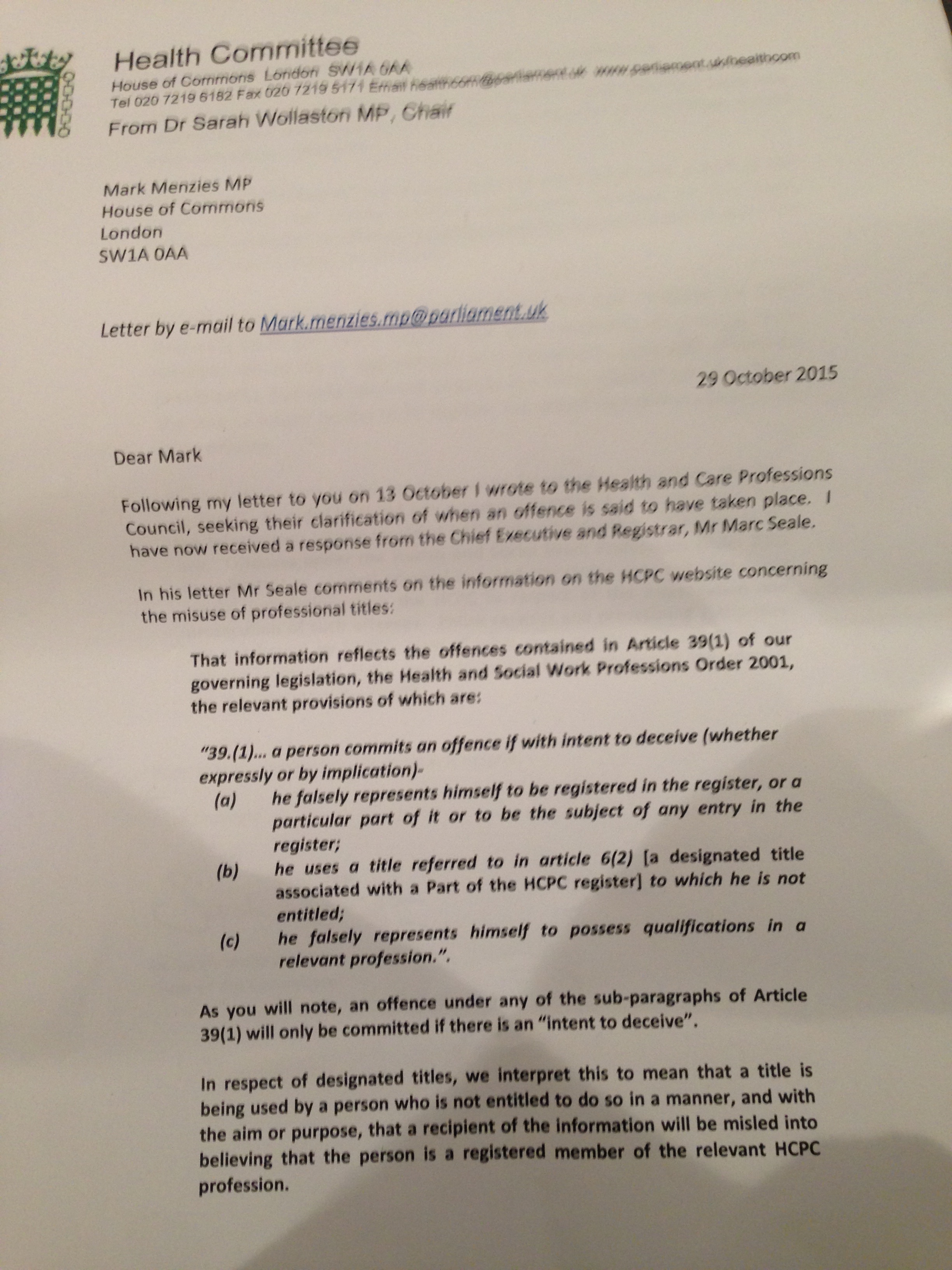

My local MP had become involved. Mark Menzies had written to various Ministers about the case and I was grateful for his support – but no one in Government was willing to become involved when legal proceedings were still in force. In October last year, Lancaster, Dr Sarah Wollaston MP, the Chair of the Common’s Health Select Committee wrote to Marc Seale, the Registrar at the HCPC to ask for clarification about the legislation. He replied:

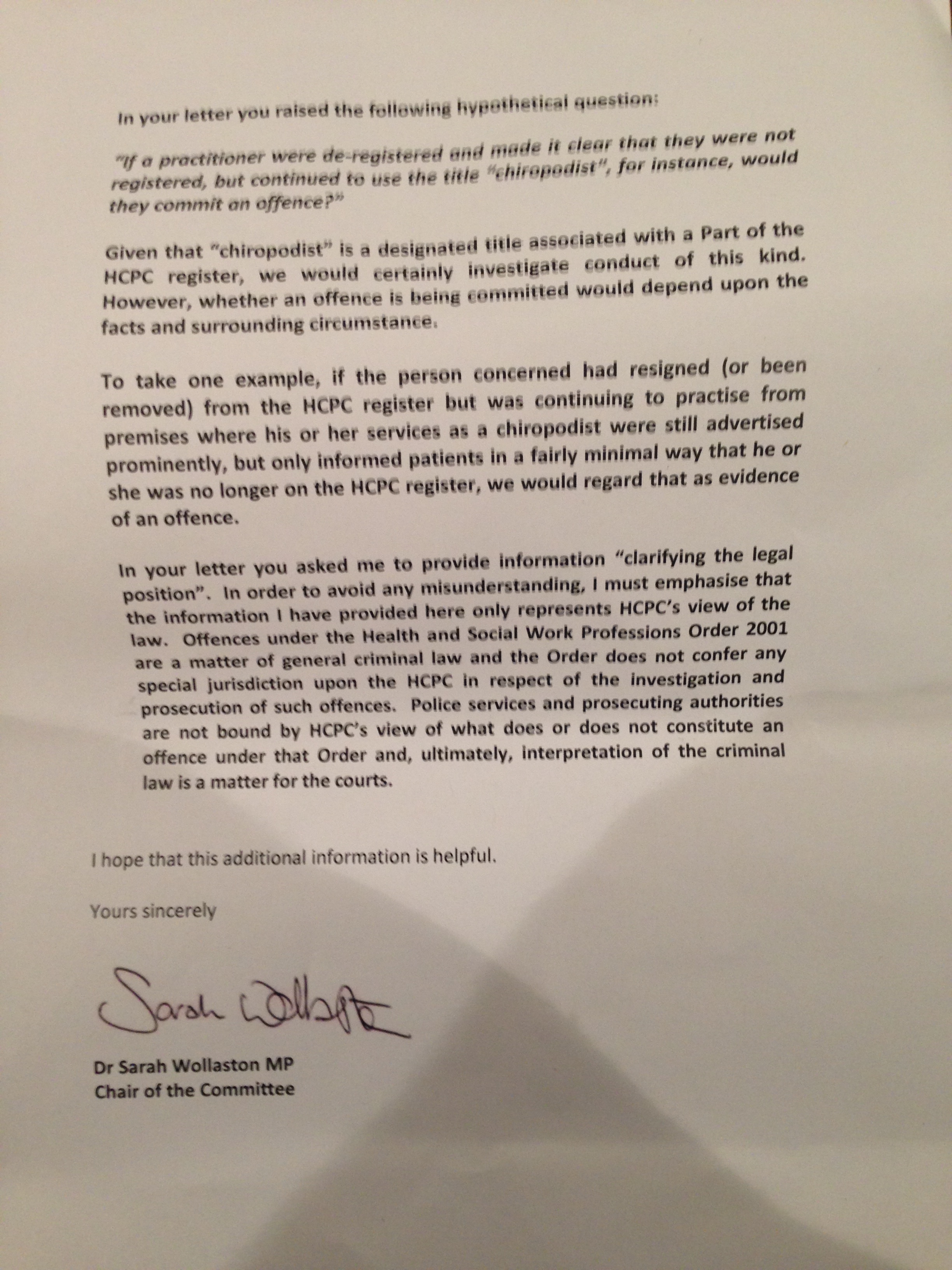

“In your letter, you raised the following hypothetical question:

If a practitioner de-registered and made it clear they they were not registered, but continued to use the title “chiropodist”, would they commit an offence?

Given that “chiropodist” is a designated title associated with a part of the HCPC register, we would certainly investigate conduct of this kind. However, whether an offence is being committed would depend upon the facts and the surrounding circumstances.

To take one example, if the person concerned had resigned) or been removed) from the register but was continuing to practice from premises where his or her services as a chiropodist were still advertised prominently, but only informed patients in a fairly minimal way that he or she was no longer on the HCPC register, we would regard that as evidence of an offence”

This was the first time the Registrar had publicly acknowledged that there are circumstances where someone could legally use a “designated” title without registration – where they took adequate precautions to inform patients, public, colleagues that they were practising without registration. Which is exactly what I did. I wasn’t made aware that I could or should promote the fact widely that I had ceased registration – but I had done so in any event. I thought I was breaking the law and as it had a professional connection, I felt I had a duty to inform not only all my patients that had sufficient capacity to understand the issue but also anyone who knew me in a professional capacity. Many people knew me as a registered podiatrist; it was only right and proper to let them know what I had done – and why.

However, I didn’t receive a copy of Dr Wollaston’s letter until early December and by that time the appeal was already underway.

The case was listed for two days at Lancaster Castle. Two days before the hearing my solicitor informed me that he had discovered there was a problem when the summons was first issued in London and that it might not even be valid. If that were the case then the conviction would automatically be overturned. Three colleagues had helped meet my legal costs for the two-day hearing and the prospect of it finishing early was certainly attractive. He suggested submitting an application for the court to consider and I agreed.

The appeal was due to start on Thursday 1st October at 10am, but unfortunately we were delayed when the Judge’s car broke down on the way to court and we didn’t start until 11.40am. A legal discussion ensued about the summons and continued into the afternoon until the Judge dismissed the application at 3.20pm. We then rose for the day.

The Prosecution presents its case the following morning. There were no witnesses and the evidence is all paperwork – documents, letters, statements etc. Once again I was characterized as a mischievous individual who embarked on a political campaign to undermine the HCPC and conducted myself dishonestly by misleading and deceiving my patients and the general public. The Judge questioned him extensively and one question I recall with clarity was almost exactly the same as Dr Wollaston was to ask of the Registrar of the HCPC later that month.

“If a chiropodist de-registered continued to use the title “chiropodist” but made it clear that they were not registered in a publicly accessible document, would that constitute an offence?

The Prosecution QC confirmed that it would not and I wondered what on earth this was really all about. I had been expecting to give evidence that day, but the Prosecution case lasted until 3.10pm and the Judge decided another day was required to hear the defence case and closing arguments – and adjourned the appeal until 10th December in Preston.

I was absolutely despondent. When I stopped full-time practice, I thought it would be no more than a few weeks before the HCPC would correct their website – but even after the Old Bailey appeal it remained on public view. Eighteen months later and I’m told it will take another eight weeks before the matter is resolved and I realise it will be two years since my practice closed and what future prospects I had of recovering my business was fading rapidly.

Coupled with that, the stress and pressure of trying to deal with the prosecution and its effects was having an enormous impact not only on myself, but those around me too and a few days after the appeal was adjourned in Lancaster, a seven-year relationship came to an end and the misery of waiting another eight weeks until the nightmare finished was compounded even further – and for the first time in my life, I was aware of slipping into a dark place.

I tried to keep busy by going over all the evidence to see if I could make some sense of it. On one hand, the answer to the Judge’s question was unequivocal and as I had literally dozens of articles and internet posts – all publicly accessible – stating I was no longer registered and why, then clearly I hadn’t committed an offence. But I was concerned about two things.

The evidence that was considered unreliable in the first trial – the complaints solicited by the Osteopath, had been re-introduced into the evidence and was referred to by the Prosecution to demonstrate that I was still referring to myself as a Registered Podiatrist after I ceased affiliation – which I had never done. The court was also told that I was well aware of the “intent to deceive” element of the offence and that I could have avoided prosecution if I had just called myself an “unregistered podiatrist” from the start. But that was manifestly untrue. I had seen the “intent to deceive” in the legislation and in letters from the HCPC many times, but its significance in relation to the offence had never been highlighted or explained by the regulator, or at least, not to me. I would have expected the HCPC to tell me what I needed to do to comply with the legislation when I told them I was de-registering – that if I was going to call myself a podiatrist, I had to ensure nobody could be deceived or misled into thinking I was registered, otherwise I would commit an offence. But they didn’t – and eight years later a court is being told that I “must have known” about the necessary requirements of the offence and had I written “unregistered” on practice stationery then this hugely expensive prosecution would have been avoided. I had the feeling that an apology was not on the cards.

A week after the appeal was adjourned in October, I wrote to the Chief Executive of my old professional body, the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists and asked if Council would issue me with a statement to confirm that my understanding of the regulation was consistent with that of the rest of the profession, from the information provided by the HCPC. Three weeks later I received an email to inform me that Council did not think it would be appropriate to become involved in the case. A few days later, my MP sent me a copy of the correspondence from Dr Wollaston and I was as confused as ever.

During November, colleagues organized a few fundraising events and I was again humbled by their generosity and support as they raised enough to cover the legal costs of the final hearing in December. I borrow some more from friends so I can survive through until Christmas, when hopefully, I will be able to recover my legal costs to date and repay all those who have been so kind.

I gave evidence before being cross-examined by the prosecution. I was taken through the evidence and I stress once again that I did not intend to deceive or mislead anyone. I was asked why I did not use “unregistered” on practice material such as business cards and letters instead of being “silent” on the matter, but of course, no one had told me that I could. When I told the court that the HCPC had concealed the important relevance of the “intent to deceive” requirement in the legislation from not only myself, but all the professions they regulate – and the first admission from the regulator that this had to be fulfilled for an offence to be committed was at the Old Bailey – the Prosecutor dismissed the claim as “nonsense”. It was obvious that the Judge shared the Prosecutor’s view. When I suggested the documents and the complaints solicited by the osteopath were fabricated and malicious, it was clear that I was not believed.

I finished giving evidence at 2.45pm and had two other witnesses to call, however the Judge had a prior engagement in London that evening and decided to finish early and adjourned the case until 22nd April 2016 to hear the final witnesses and closing arguments. I was thoroughly dejected and incredulous that the case had still not finished. This had been my ninth appearance in court at an average cost of £3,000 per day and the prospect of surviving another five months without any income seemed impossible. What’s more, the Judge’s reaction to my evidence did not fill me with much confidence for a successful outcome, as it was clear that she considered my assertion, that the HCPC had concealed the true nature of the offence, implausible. For the third year in a row, the Festive period was spent under a dark cloud of depression, isolation and insomnia.

I had started to record a diary of events the previous year and regularly updated my website to keep colleagues and patients abreast of developments in the trial – but it was evident that my commentary of proceedings was not appreciated by the court. As the case progressed, I received many letters and emails from colleagues across the professions who were astonished by the revelations that were unfolding – particularly in respect of the “protected” titles. It was clear that I was not mistaken in my belief that the HCPC had never explained the absolute necessity of an “intent to deceive” when claiming the titles were “protected” in law and that the offence was one of strict liability. If that was correct, then this raised the possibility that the HCPC had fraudulently misrepresented the regulatory position to the professions from the day it was established. The Registrar’s letter to the Health Committee Chair was an explanation of the legislative provision for designated titles. He did not say that it was a revised position nor that his organisation had consistently neglected to explain the requirements of the legislation before then. In court, my suggestion that they had was met with derision.

The first couple of months of this year were extremely difficult. I was astonished by the intermittent progress of the case; six hours in court followed by months of anxious waiting for another hearing – and what was estimated to take two days for an appeal would now run into its fourth day spread over seven months. By now, the case was approaching its third anniversary.

Many of my colleagues who had attended court during the trial and appeal were shocked to hear the prosecution suggest that there had been no concealment by the HCPC. That was clearly untrue. In April, a few weeks before the final hearing, over two-dozen registered podiatrists wrote independently to the Judge to express their own opinion that the HCPC had never advanced the actual legislative position before and their views were consistent with my own. I asked Ralph Graham, Chairman of the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists during the period when the regulatory regime was being introduced, to comment. Ralph was also the Chair of the Allied Health Federation and was highly respected across the professions and the NHS. He kindly offered a Witness Statement, which explained in detail what our profession had been led to believe.

In addition to confirming my own position, his statement also illuminated another issue and this perhaps offers an explanation why the regulator acted to conceal the “intent to deceive” in the first place. Regarding discussions the profession had with the regulator and government officials, he wrote:

Part of those discussions related to protection of title. The profession was obliged to admit as equals on the new register several thousand previously unregistered chiropodists. These had not been eligible under CPSM rules because they had not attended fulltime education. They were to be “grandfathered” on to the new HCPC register during a three year window if they were in full time practice on the date the HCPC came into existence.

This was considered a great price by those already on the register following 3-year degree courses and was unpopular among the profession. After the grandfather process was closed the only way onto the register would be via University degrees. The only attraction to this process was that the Health Professions Orders gave protection of title. We were assured the named titles would be reserved for those registered with the HCPC and ‘that it would be an offence to use such a title without being on the HCPC register’. I have no recollection whatsoever of the requirement ‘intent to deceive’ ever being mentioned.

We were informed that only two titles per profession would be protected and despite our wish to see the European title podologist also protected this was denied. The information was clear, the use of the agreed protected titles (without registration) would be an offence.

I have provided HCPC documents for the court and these make no mention of any requirement to intend to deceive. I also have provided documents from a review of the regulatory process by the Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence (CHRE) which again in examining cases against unregistered persons for misuse of protected titles makes no mention of any requirement to show ‘intent to deceive’.

I have spoken with a colleague who was appointed to the first HCPC Council who confirms that my understanding of the position and hers are the same, that the offence is simply to use one of the designated (protected) titles.

I now understand that the Health Professions Orders require intent to deceive thus it would be possible to use a designated title in combination with a statement such ‘not registered with the HCPC’ to evade the intention of the Orders. If this had been apparent in 2003 it is highly likely that the profession would have been persuaded by those arguing to refuse to register with the HCPC.

And of course, that would have meant the loss of up to £1 million annually in registration fees from those in the podiatry profession – and that is always the predominant consideration these days. It would also represent a breach of promise – and trust – that was implied during the negotiations and consultation period; that the professional titles would be fully protected by the HCPC in the proposed regime. The professions were sold a lie.

When the court reconvened on 22 April 2016, the Judge was clearly annoyed that colleagues had written independently to her and said that she was disregarding all the correspondence as irrelevant. Ralph Graham’s statement was served on the Prosecution in early April, but unfortunately he was on holiday later in the month and was not able to attend court in person. His statement, however, was also given to the Judge by the prosecution – but this was dismissed as irrelevant too.

I was surprised at this. Under cross-examination at the previous hearing the prosecution averred that it was nonsense when I stated the profession had been misled by the HCPC and did not understand the significance of the intent to deceive element. I would have thought that a corroborating witness statement from an authoritative source would have been of some significance, especially if the court had been unclear about the history when the regulation was introduced.

To me, this was the central issue in the case. The HCPC had concealed an important part of the offence to create the mistaken impression that the mischief was simply using a title without being registered. Why else would I have pleaded guilty at the first trial? From that perspective, the evidence takes on a completely different hue.

The rest of the day was spent hearing more evidence from my witnesses and then the closing arguments after lunch. We had been told that morning that a verdict would be reached that day, but after hearing both Counsels, the Judge decided she would like more time to consider the evidence and adjourned the case again until 29th June.

This had turned into a sick farce long ago. I kept expecting someone from the HCPC to appear and say how dreadfully sorry they were and that they had made an unfortunate mistake, but that was never going to happen. That would be what most ordinary people would do, if they were honest. But that’s not how Government and its agencies work these days. There it is obfuscation rather than clarity and concealment instead of transparency. And a willingness to use the legal system to intimidate and punish anyone prepared to speak out when they dare to raise a concern. It’s just a game after all – where the preserving the system becomes more important than any individual consideration. I’ve had my reputation traduced, my honesty questioned and had been branded deceitful by a statutory authority whose own conduct has been that and more.

I don’t care to dwell on the impact this prosecution has made on me personally, suffice to say it has been profound and of a magnitude I did not expect. There will have to be a time for recovery, but that would now have to wait another two months, at least.

On 29th June 2016, Her Honour Justice Beech delivered a narrative and written verdict. This was my eleventh court appearance in total, nine of which my only objective was to correct the misleading claim that I had acted to deceive. However, I was found guilty again. Within the judgement, it noted:

“Mr Russell maintained that he did not understand the wording of the offence despite the fact that he had taken an avid interest in the legislation and had lobbied the Scottish Parliament on it and that when he was a member of the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists, he had been a member of the Legislative Affairs Committee and in that role, he had scrutinised the legislation.

The Next issue is whether Mr Russell appreciated the true import of paragraph 39(1) of the 2001 Order in that it involved an intention to deceive. We repeat that Mr Russell is an intelligent man. He has been a member of the Legislative Affairs Committee of the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists and had taken a great deal of interest in the proposed regime and the legislation.

We find his evidence on this point is incredible and not worthy of belief.”

The judge went on to say of me:

“his declarations have been inconsistent…”

“he has not impressed us as a witness”

“his answers to difficult questions have been unbelievable…”

“that explanation was nonsense…”

“Mr Russell is audacious and misleading to say the least…”

“Meaningless and deceitful”…

“We find a textbook case of ‘smoke and mirrors’..”

This judgement was predicated on the notion that I must have understood the wording of the legislation and with that knowledge, I had acted dishonestly and deceived patients and the public into thinking I was registered when I was not – with the motive of funding a misconceived political campaign to undermine the HCPC. That is clearly wrong.

The fine of £200 remains and I was ordered to pay a total of £2,000 towards the HCPC’s costs

I completely reject this verdict and with all due respect to the court, I consider it perverse.

I am unable to progress this case any further as I have long since run out of money and I am unwilling to borrow any more. Even if I could, I doubt if I would consider an appeal to a higher court as I now have just about as much faith in the criminal justice system as I do with medical regulation and governance.

I do however, have some questions and would like to make a few polite requests:

To Mr Marc Seale, Registrar at the HCPC:

1. Why have you concealed the importance of the intent to deceive element of the offence from the professions until last year?

2. Why did you not advise me, when I ceased registration, that I could practice, lawfully, as an unregistered podiatrist, provided I took every precaution not to deceive anyone?

3. Why did you repeatedly send me “cease and desist” letters threatening prosecution when you were aware that I was complying fully with the legislation?

4. What justification is there for spending hundreds of thousands of pounds of registrant’s money to prosecute an individual for simply raising a concern?

5. Will you publicly acknowledge that your organisation cannot prevent individuals who have been struck-off the register from continuing in practice under a non-designated title – and when that occurs, those individuals continue to endanger the public with the risk that you identified in the first place?

6. Will you take immediate steps to inform the Court that I could not possibly have known that the offence was conditional on an accompanying “intent to deceive”?

7. Will you, as the prosecuting authority, seek leave to appeal this conviction on my behalf on the grounds that the evidence submitted in court by your legal agents was factually wrong?

To Rt. Hon. Jeremy Hunt, Health Secretary:

1. You have stated repeatedly that everyone in healthcare should speak up when we identify circumstances that endanger public safety. When we do, what response should we expect?

2. Speaking up has cost me £342,000 in legal costs and loss of earnings. I have lost my practice, savings and livelihood and in three weeks time, I will be homeless. I have been branded dishonest and deceitful and dragged through a nightmare by a health regulator intent on covering-up its own failings. What message does that send to anyone in the health or care professions who may be faced with the dilemma of reporting dangerous practice that endangers public safety?

3. Will you acknowledge that the health professions regulated by the HCPC and NMC were not fully and properly informed about the scope of the legislation in relation to the offences for the misuse of titles – and will you take steps to ensure the “intent to deceive” requirement is removed so that the designated professional titles are properly protected in law?

4. Will you also undertake to address the risk that is clearly evident in private sector provision from unregistered and unregulated clinicians who have been struck-off the statutory register for serious misconduct or dangerous practice?

5. What safeguards can be considered for whistleblowers in the private sector or for those who are self-employed who remain vulnerable to punitive and malicious practice from public institutions with powers to prosecute?

Finally, I once again thank all my colleagues and friends who have shown incredible generosity and support over the last three years – without it I wouldn’t be here now. I am especially grateful to those who have travelled far and often to watch this charade and just to be there.

One final request to visitors who are registrants of the HCPC.

Were you aware of the necessary requirement of “an intent to deceive” to commit an offence of Misuse of Title before this prosecution?

I would be grateful if you can leave your answer in the comments.

![lochnagar-crater-5[2]](http://mark-russell.net/Blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/lochnagar-crater-52.jpg)