There’s a climb high up on Ben Nevis, where the crux move is over an overhang at the top of a vertical corner six hundred feet above the screes. There’s a small hold for the right hand two feet above the lip, but you have to reach it in one move – and that means letting go of both hands that are wedged into the crack underneath the two feet of granite you keep banging your head on.

Two feet out and two feet up and six hundred below. And you’re getting cramp in both legs that are spread as wide as possible so you can arch your back and peer nervously over the lip. Not a place for a selfie….

What’s required is a huge amount of courage, determination, strength – and most importantly, belief. Belief that the hold is there and you can make it. Belief that it will give you the momentum to keep going up the steep crack above for the next ten feet to the big ledge and salvation. Belief that you won’t fall off.

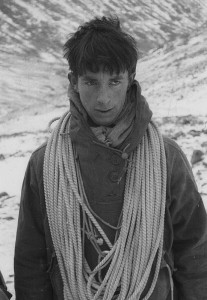

It’s called the Bat (coined by Robin Smith on account of Dougal Haston’s impersonation of the wee beastie each time he fell off during the first ascent in 1959) – and I regret to say I’ve never been able to lead it and never will. Not through any lack of belief – only ability and strength. And decrepitude!

But I still think about it from time to time.

Perhaps when the time is right…

THE BAT AND THE WICKED

By Robin Smith (1960)

You got to go with the times. I went by the Halfway Lochan over the shoulder of Ben Nevis and I got to the Hut about two in the morning. Dick was there before me; we had to talk in whispers because old men were sleeping in the other beds. Next day we went up Sassenach and Centurion to spy on the little secrets hidden between them. We came down in the dark, and so next day it was so late before we were back on the hill that the big heat of our wicked scheme was fizzling away.

Carn Dearg Buttress sits like a black haystack split up the front by two great lines. Centurion rises straight up the middle, 500ft. in a vast corner running out into slabs and over the traverse of Route II and 200ft. threading the roofs above. Sassenach is close to the clean-cut right edge of the cliff, 200ft. through a barrier of overhangs, 200ft. in an overhanging chimney and 500ft. in a wide broken slowly easing corner. At the bottom a great dripping overhang leans out over the 100ft of intervening ground. Above this, tiers of overlapping shelves like armour plating sweep out of the corner of Centurion diagonally up to the right to peter out against the monstrous bulge of the wall on the left of the Sassenach chimney. And hung in the middle of this bulging wall is the Corner, cutting through 100ft of the bulge. Dick and I lay and swithered on a flat stone. We wanted to find a way out of Centurion over the shelves and over the bulge into the Corner and up the Corner and straight on by a line of grooves running all the way over the top of the Buttress, only now it was after two in the afternoon.

But we thought we ought just to have a look, so we climbed the first pitch of Centurion, 50ft. to a ledge on the left. The first twisted shelf on the right was not at all for us, so we followed the corner a little farther and broke out rightwards over a slab on a wandering line of holds, and as the slab heeled over into the overlap below, a break in the overlap above led to the start of a higher shelf and we followed this till it tapered away to a jammed block poking into the monstrous bulge above. For a little while Dick had a theory that he felt unlike leading, but I put on all the running belays just before the hard bits so that he was in for the bigger swing away down over the bottom dripping overhang. We were so frightened that we shattered ourselves fiddling pebbles and jamming knots for runners. We swung down backwards in to an overlap and down to the right to a lower shelf and followed it over a fiendish step to crouch on a tiny triangular slab tucked under the bulge, and here we could just unfold enough to reach into a V-groove, cutting through the bottom of the bulge and letting us out on a slab on the right just left of the Sassenach chimney.

And so we had found a way over the shelves, but only to go into orbit round the bulging wall with still about 40ft. of bulge between us and the bottom of the Corner now up on the left. The way to go was very plain to see, a crooked little lichenous overhanging groove looking as happy as a hoodie crow. But it looked as though it was getting late and all the belays we could see were very lousy and we might get up the groove and then have to abseil and underneath were 200ft of overhangs and anyway we would be back in the morning. We could just see the top of the Corner leering down at us over the bulge as we slunk round the edge on the right to the foot of the Sassenach chimney. A great old-fashioned battle with fearful constrictions and rattling chockstones brought us out of the chimney into night, and from there we groped our way on our memory of the day before, leading through in 150ft run-outs and looking for belays and failing to find them and tying on to lumps of grass and little stones lying on the ledges. When we came over the top we made away to the left and down the bed of Number Five Gully to find the door of the Hut in the wee small hours.

We woke in the afternoon to the whine of the Death Wind fleeing down the Allt a’ Mhuillin. Fingery mists were creeping in at the five windows. Great grey spirals of rain were boring into the Buttress. We stuck our hands in our pockets and our heads between our shoulders and stomped off down the path under our rucksacks into the bright lights of the big city.

Well the summer went away and we all went to the Alps. (Dick had gone and failed his exams and was living in a hole until the re-sits, he was scrubbed.) The rest of the boys were extradited earlier than I was, sweeping north from the Channel with a pause in Wales in the Llanberis Pass at a daily rate of four apiece of climbs that Englishmen call xs (x is a variable, from exceptionally or extremely through very or hardily to merely or mildly severe). From there they never stopped until they came to Fort William, but the big black Ben was sitting in the clouds in the huff and bucketing rain and the rocks never dried until their holidays ended and I came home and only students and wasters were left on the hill.

Well I was the only climber Dougal could find and the only climber I could find was Dougal, so we swallowed a very mutual aversion to gain the greater end of a. sort of start over the rest of the field. Even so we had little time for the Ben. We could no more go for a weekend than anyone else, for as from the time that a fellow Cunningham showed us the rules we were drawn like iron filings to Jacksonville in the shadow of the Buachaille for the big-time inter-city pontoon school of a Saturday night. And then we had no transport and Dougal was living on the dole, and so to my disgust he would leave me on a Wednesday to hitch-hike back to Edinburgh in time to pick up his moneys on a Thursday. The first time we went away we had a bad Saturday night, we were late getting out on the Buachaille on Sunday and came down in the dark in a bit of rain. But the rain came to nothing, so we made our way to the Fort on Monday thinking of climbing to the Hut for the night; only there was something great showing at the pictures and then we went for chip suppers and then there were the birds and the juke-box and the slot machines and we ended up in a back-garden shed. But on Tuesday we got up in the morning, and since Dougal was going home next day we took nothing for the Hut, just our climbing gear like a bundle of stings and made a beeline for Carn Dearg Buttress.

This time we went over the shelves no bother at all, until we stood looking into the little green hoodie groove. It ran into a roof and from under the roof we would have to get out on the left on to what looked as though it might be a slab crossing to the bottom of the Corner. I was scheming to myself, now the groove will be terrible but nothing to the Corner and I will surely have to lead the crux, but Dougal shamed me with indifference and sent me round the edge on the right to find a decent belay under the Sassenach chimney. There it was very peaceful, I could see none of the tigering, only the red stripes down the side of Carn Mor Dearg running into the Allt a’ Mhuillin that was putting me to sleep if there hadn’t been odd faint snarls and scrabblings and little bits of rope once in a while tugging around the small of my back. But once Dougal was up he took in so much slack that I had to go and follow it myself. Half-way up he told me, you lean away out and loop a sling over the tip of a spike and do a can-can move to get a foot in the sling and reach for the sling with both hands as you lurch out of the groove and when you stop swinging climb up the sling until you can step back into the groove; and his sling had rolled off the spike as he left it, so I would have to put it on again. I came out at the top of the groove in a row of convulsions, which multiplied like a spastic as I took in the new perspective.

Dougal was belayed to pitons on the slab under the Corner. The slab and the left retaining wall went tapering down for 20ft till they merged and all heeled over into the general bulge. Above, the Corner balanced over Dougal like a blank open book with a rubber under the binding. The only big break in the bareness of the walls was a clean-cut black roof barring the width of the right wall. The crack went into the right wall, about six inches wide but tightly packed with bits of filling; and thus it rose in two leaps, 35ft. to the black roof, then out four horizontal feet and straight up 35ft. again; and then it widened for the last 30ft. as the right wall came swelling out in a bulge to meet the top of the great arc of the sky-line edge of the left wall. And if we could only get there then all the climb would surely be in the bag.

Well I had stolen the lead, only some time before I had been to a place called Harrison’s Rocks and some or other fellow out of London had made off with my PA’s. Now PA’s are the Achilles’ Heel of all the new men, they buckle your feet into claws and turn you into a tiger, but here I had only a flabby pair of kletterschuhe with nails sticking out on both sides of the soles, and so I worked on Dougal to change footwear at which he was not pleased because we stood on a steep slab with one little ledge for feet and a vision before us of retreating in our socks. We had two full-weight ropes. Dougal had one rope that was old before its time, it had once been 120ft long but it lost five feet during an experiment on the Currie Railway Walls. (This last word to sound like `Woz’.) A Glaswegian who was a friend had one day loaned us the other, and so it was even older, and he mentioned that it had been stretched a little, indeed it was 130ft. long, and so Dougal at the bottom had quickly tied on to an end of each rope which left me with 15ft on the one to get rid of round and round my middle to make the two ropes even. This was confusing, since I had a good dozen slings and karabiners round my neck and two bunches of pitons like bananas at my waist and a wooden wedge and a piton hammer swinging about and three or four spare karabiners and a big sling knotted into steps.

But I could still get my hands to the rocks, and I made slow progress as far as the black roof. I left about six feeble running belays on the way, mainly so that I would be able to breathe. And as there seemed little chance of runners above and little value in those below and nowhere to stand just under the roof and next to no chance of moving up for a while, I took a fat channel peg and drove it to the hilt into the corner crack as high under the roof as I could and fixed it as a runner and hung the knotted sling from it and stood with my right foot in the sling. Thus with my hands in the crack where it came out horizontally under the roof, I could plant my left foot fictitiously away out on the left wall and peer round over the roof into the Corner above. Deep dismay.

The crack looked very useless and the walls utterly bare and I shrunk under the roof into the sling. Shortly I leaned away out again to ponder a certain move and a little twist and then something else to get me 10ft. up. but what would I do then, and then the prepondering angle sent me scuttling back like a crab into shelter. In a while I got a grip and left the sling and heaved up half-way round the roof and sent a hand up the Corner exploring for a hold, but I thought, no no there is nothing at all, and I came down starting with a foot under the roof feverishly fishing for the sling. And there I hung like a brooding ape, maybe there’s a runner 10ft up or a secret keyhole for the fingers, but how are you ever to know for sitting primevally here, so for shame now where’s your boldness, see how good your piton is, and what’s in a peel, think of the Club, think of the glory, be a devil. I found a notch under the roof in which to jam the knot of a sling which made another runner, and I tried going up a few more times like a ball stopping bouncing until I realised I was going nowhere and trying nothing at all. So I jacked it in and left all the runners for Dougal and Dougal let out slack and I dribbled down to join him on the slab.

Here I sat a while and blew, then I took my coat of mail and put it on Dougal and Dougal wanted his PA’s back and we untied to swop our end of rope so that Dougal could use my runners and I tied myself on to the stance while Dougal rotated into the tail end of the longer rope and the time went by. But Dougal caught it up a little by rushing up to the black roof while I pulleyed in the slack. And here we had a plan. Just above the lip of the roof, the crack opened into a pocket about an inch and a quarter wide. There should have been a chockstone in it, only there was not, and we could find none the right size to insert. If there had been trees on the Ben the way there are in Wales there would have been a tree growing out of the pocket, or at least down at the stance or close to hand so that we could have lopped off a branch and stuck it in the pocket. But here we had a wooden wedge tapering just to the right size and surely it once grew in a tree and so maybe it would not be very artificial to see if it could be made to stick in the pocket. Blows of the hammer did this thing, and Dougal clipped in a karabiner and threaded a sling and the two ropes and pulled up to stand in the sling so that he could reach well over the roof and look about at ease. And sure enough he could see a winking ledge, about 25ft. up on the right wall.

Now Dougal is a bit thick and very bold, he never stopped to think, he put bits of left arm and leg in the crack and the rest of him over the right wall and beat the rock ferociously and moved in staccato shuffles out of the sling and up the Corner. I shifted uneasily upon my slab which tapered into the overhangs. making eyes at my two little piton belays. As Dougal neared his ledge he was slowing down but flailing all the more, left fingers clawing at grass in the crack and right leg scything moss on the wall. I pulled down the sleeves of my jersey over my hands and took a great grip of the ropes. Then there came a sort of squawk as Dougal found that his ledge was not. He got a hand on it but it all sloped. Rattling sounds came from his throat or nails or something. In his last throes to bridge he threw his right foot at a straw away out on the right wall. Then his fingers went to butter. It began under control as the bit of news “I’m off,” but it must have been caught in the wind, for it grew like a wailing siren to a bloodcurdling scream as a black and bat-like shape came hurtling over the roof with legs splayed like webbed wings and hands hooked like a vampire. I flattened my ears and curled up rigid into a bristling ball, then I was lifted off my slab and rose five feet in the air until we met head to foot and buffered to a stop hanging from the runners at the roof. I could have sworn that his teeth were fangs and his eyes were big red orbs. We lowered ourselves to the slab, and there we sat in a swound while the shadows grew.

But indeed it was getting very late, and so I being a little less shattered heaved up on the ropes to retrieve the gear, leaving the wedge and the piton at the roof. We fixed a sling to one of the belay pitons and abseiled down the groove below with tails between our legs and a swing at the bottom to take us round to the foot of the Sassenach chimney. By now it was dusk and we thought it would be chaos in the chimney and just below it was very overhanging, but I knew a traversing line above the great roof of Sassenach leading to the clean-cut right edge of the cliff. My kletterschuhe kept slipping about and I was climbing like a stiff and I put in two or three tips of pitons for psychological runners before I made the 50ft. of progress to peer around the edge. But it looked a good 200ft to the shadowy screes at the bottom, and I scuffled back in half a panic out of the frying pan into the chimney. Then two English voices that were living in a tent came up the hill to ask if we were worried. We said we were laughing but what was the time, and they said it would soon be the middle of the night, and when we thought about the 700ft of Sassenach above and all the shambles round the side to get to our big boots sitting at the bottom of the cliff, we thought we would just slide to the end of the rope.

So I went back to the edge and round the right angle and down a bit of the wall on the far side to a ledge and a fat crack for a piton. By the time Dougal joined me we could only see a few dismal stars and sky-lines and a light in the English tent. Dougal vanished down a single rope while I belayed him on the other, and just as the belaying rope ran out I heard a long squelch and murky oaths. He seemed to be down and so I followed. Suddenly my feet shot away and I swung in under the great roof and spiralled down till I landed up to my knees in a black bog. We found our boots under Centurion and made off down the hill past the English tent to tell them we were living. When we hit the streets we followed our noses straight to our sleeping bags in the shed, leaving the city night, life alone.

The next Sunday we left a lot of enemies in Jacksonville and took a lift with the Mountain Rescue round to Fort William. They were saying they might be back to take us away as well. We had thick wads of notes but nothing to eat, and so we had to wait in the city to buy stores on Monday, and we got to the Hut so late that we thought we would house our energies to give us the chance of an early start in the morning. Even so we might have slept right through Tuesday but for the din of a mighty file of pilgrims winding up the Allt a’ Mhuillin making for Ben Nevis. We stumbled out rubbing our eyes and stood looking evil in the doorway, so that nobody called in, and then we ate and went out late in the day to the big black Buttress.

This time we went over the shelves and up the hoodie groove no bother at all. It was my turn to go into the Corner. By now I had a pair of PA’s. I climbed to the black roof and made three runners with a jammed knot, the piton and the wooden wedge and stood in a sling clipped to the wedge. Dougal’s ledge was fluttering above but it fooled nobody now. At full stretch I could reach two pebbles sitting in a thin bit of the crack and pinched them together to jam. Then I felt a lurch in my stomach like flying through an air pocket. When I looked at the wedge I could have sworn. it had moved. I seized a baby nylon sling and desperately threaded it round the pebbles. And then I was gracefully plucked from the rock to stop 20ft under the roof hanging from the piton and the jammed knot with the traitor wedge hanging from me and a sling round the pebbles sticking out of the Corner far above. I rushed back to the roof in a rage and made a strange manoeuvre to get round the roof and reach the sling and clip in a karabiner and various ropes, then trying not to think, I hauled up to sit in slings which seemed like a table of kings all to come down from the same two pebbles. I moved on hastily, but I felt neither strong nor bold, and so I took a piton and hammered it into the Corner about 20ft. above the roof. Happily I pulled up, and it leaped out with a squeal of delight and gave me no time to squeal at all before I found myself swinging about under the miserable roof again. The pebbles had held firm, but that meant I hung straight down from the lip of the roof and out from the Corner below so that Dougal had to lower me right to the bottom.

By now the night was creeping in. Peels were no longer upsetting, but Dougal was fed up with sitting on a slab and wanted to go down for a brew. But that was all very well, he was going home in the morning, and then coming back for a whole week with a host of terrible tigers when I would have to be sitting exams. So I was very sly and said we had to get the gear and climbed past the roof to the sling at the pebbles leaving all the gear in place. There I was so exhausted that I put in a piton, only it was very low, and I thought, so am I, peccavi, peccabo, and I put in another and rose indiscriminately until to my surprise I was past Dougal’s ledge and still on the rock in a place to rest beside a solid chockstone. Sweat was pouring out of me, frosting at my waist in the frozen mutterings flowing up the rope from Dougal. Overhead the right wall was swelling out like a bull-frog, but the cracks grew to a tight shallow chimney in which it was even blacker than the rest of the night. I squeezed in and pulled on a real hold, and a vast block slid down and sat on my head. Dougal tried to hide on his slab, I wobbled my head and the block rolled down my back, and then there was a deathly hush until it thundered on to the screes and made for the Hut like a fireball. I wriggled my last slings round chockstones and myself round the last of the bulges and I came out of the Corner fighting into the light of half a moon rising over the North-East Buttress. All around there were ledges and great good holds and bewildering easy angles, and I lashed myself to about six belays.

Dougal followed in the moonshade, in too great a hurry and too blinded and miserable to pass the time taking out the pitons, and so they are still there turning to rust, creeping up the cliff like poison ivy. Heated up by the time he passed me, Dougal went into a long groove out of the moon but not steep and brought me up to the left end of a terrace above the chimney of Sassenach. We could see the grooves we should have climbed in a long line above us, but only as thick black shadows against .the shiny bulges, and so we went right and grovelled up in the final corner of Sassenach where I knew the way to go. The wall on the left kept sticking out and stealing all the moonlight, but we took our belays right out on the clean-cut right edge of the cliff so that we could squat in the moon and peer at the fabulous sights. When we came over the top we hobbled down the screes on the left to get out of our PA’s into our boots and back to the Hut from as late a night as any, so late you could hardly call it a bed-night.

Some time next day Dougal beetled off and I slowly followed to face the examiners. The tigers all came for their week. On the first day Dougal and the elder Marshall climbed Sassenach until they were one pitch up from the Terrace above the chimney, and then they thought of going left and finished by the new line of grooves. Overnight the big black clouds rolled over and drummed out the summer and it rained all week and hardly stopped until it started to snow and we put away our PA’s and went for hill-walks waiting for the winter. They say the grooves were very nice and not very hard. All that was needed to make a whole new climb was one pitch from the terrace above the chimney, until we decided that the way we had been leaving the terrace as from the time that Dick found it when we first climbed Sassenach was not really part of Sassenach at all. By this means we put an end to this unscrupulous first ascent. The next team will climb it all no bother at all, except that they will complain that they couldn’t get their fingers into the holds filled up with pitons.

from THE SCOTTISH MOUNTAINEERING CLUB JOURNAL 1960