(First published 7 October 2015)

I was nine years old the first time I remember visiting a hospital. It was late 1970 and my maternal grandmother just had an operation on her right foot to remove a painful bunion, something my father explained, was a lump on the side of her foot. She had the procedure carried out at the Bridge of Earn Orthopaedic Hospital, a familiar landmark to many, its wartime single storey buildings situated just east of the M90 motorway as it crosses the River Earn, just south of Perth. The hospital was constructed at the beginning of the Second World War to deal with the expected casualties from the fighting and opened in 1940 with space for 1,020 patients. Early admissions came mainly from neighbouring military camps, and the lack of expected air raids led to beds being used by three British General Hospitals, patients with tuberculosis and prisoners of war. The busiest time for the hospital came in 1944, initially from casualties of the V1 and V2 bombing of London, and then the Normandy invasion. Following the war in 1947, an orthopaedic unit from Larbert was transferred to Bridge of Earn and it was predominately for this discipline that the hospital gained its reputation until it finally closed in 1992.

My grandmother had a part time job as a home help and was a fit, healthy woman in her early fifties at the time of the procedure. Her foot had been troublesome for a number of years and it was becoming increasingly painful, especially during her sporting activity, lawn bowls, for which she held a great passion. My father, a chiropodist with the NHS, had spoken to the family doctor, and he arranged an appointment with the surgeon and the bunion was duly removed as an in-patient procedure some time later. I cannot recall much of the visit to see her recovering from the operation other than the smell on the ward of antiseptic, which was quite different to that in my father’s surgery or even the local dentist – and the nurses, who looked pristine in their starched white uniforms. My grandmother was sporting a below-knee plaster cast on her right leg and only her toes were visible and I remember being asked to count them in case any were missing. None were, but she had gained something extra! The operation was a simple arthrodesis; a procedure that corrects the position of the great toe and involves having part of the joint removed and a steel pin or wire inserted through the end of the toe down into the long metatarsal. This pin and the plaster cast would hold the toe in the correct position until the surgery healed in around six weeks and where the pin protruded from the end of the toe, it was capped by a small cork and it was this that held my attention for the duration of the visit. She remained in hospital for a week then returned home to convalesce until the pin and plaster cast were removed around a month later. The operation was deemed a success and a few months later she resumed her bowling with renewed enthusiasm, going on to win a number of championships and trophies in the following years. The operation was carried out on her leading foot as she was right-handed, and as such, the toe joint remained straight with the foot flat on the ground when she released her bowl. By contrast, the great toe on her trailing, left-foot was fully bent back or extended when she released and had the problem occurred on this foot and she had undergone the same procedure, then it would have been much more difficult for her to be able to return to the game she loved so much and in that respect, on this occasion, she was fortunate.

Four years later she was back in hospital for another operation. This time she was in the relatively new Victoria Hospital in Kirkcaldy – a general hospital encompassing the whole gambit of medical specialisms, but this time it was not for a minor joint problem but something altogether more serious. What she would not be aware of at the time was that this episode of ill-health would herald the circumstances of her death a dozen or so years later through a number of simple but completely avoidable mistakes by those she entrusted with her care.

Agnes Wilson was born on 2 October 1916 in the small mining village of Lochgelly in central Fife, midway between Dunfermline and Kirkcaldy. It is a date that would have some significance in my own life some ninety nine years later and is just one of a number of quite remarkable coincidences you will learn about in due course. It was a time of turmoil and slaughter in the middle of the Great War; the Somme Offensive in northern France was entering its bloodiest phase with many casualties from fighting in the Battle of Thiepval. In the collieries and pits of central Fife the outlook was just as grim. Desperate working conditions and real hardship with a dark sense of foreboding saw thousands of young men heading south to help the war effort, leaving behind families struggling to put the basics on the table – a task made even more difficult with the loss of their sons to the battlefield rather than the coalface. The coming decade at the end of the war saw little improvement in their prospects and with so many sons and fathers killed in action the future must have seemed devoid of hope for those left behind. By the time she was thirteen, Agnes had left school and was in work at the Jenny Grey Pit washing and separating coals and rubble at the pit-head where she worked for three years. She was one of five children; two sisters and two brothers and perhaps the only remarkable thing about their formative years was that they survived through into adulthood during times of high infant and child mortality arising from the poor sanitation, not to mention malnutrition and work related injuries down the pits, which were often horrific. By sixteen she had left the pits and went to work ‘in service’ in Edinburgh – cleaning mostly in some of the grand Georgian houses in the New Town where she lived in servant’s quarters before returning home to Lochgelly on her days off. Sometime during the next few years, she met my grandfather, Tom MacDonald, an apprentice blacksmith and a romance started and they were married soon after in 1938 and moved into a ground floor two-roomed tenement next door to the West School in the town. Two years later their first child appeared – my mother, followed two years later with another girl, both born at home with the doctor in attendance.

It is difficult to imagine today what living conditions were like in this working class mining village during either War when both my parents and grandparents were born. From the stories I have heard over the years it must have been unrelentingly arduous; outside toilets, food rations, freezing winters without any heating other than the coal fire – and yet these times are remembered in good terms and with fond memories. The family lived in these sparse conditions throughout the war and beyond until the incredibly harsh winter of 1947 when they moved into a brand new prefab on the edge of the village opposite the golf club. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they endured the usual childhood illnesses of the time – chicken pox, scarlet fever, mumps, influenza were all unwelcome visitors at some time or another, yet I cannot recall my grandmother or grandfather telling me of a time when they were struck down with anything that required a visit to the doctor, never mind a hospital. Until the bunion started to hurt.

I had just started secondary school in neighbouring Cowdenbeath when she started to feel unwell. It was 1973 and we had just returned from a family holiday near Oban where she had experienced several bouts of abdominal pain over the fortnight. I suspect she consulted the family doctor on her return as her first appointment with the hospital consultant coincided with my first day at Beath Junior High. It was ‘woman’s troubles’, my father explained later. And she was to have another operation.

It was over a decade later before I discovered she had ovarian cancer and that the operation was, of course, a hysterectomy, but at the time it was just another mysterious illness attributed to the fairer sex under the guise of ‘woman’s troubles’. Whispered quietly, it was a subject that was to be acknowledged but not discussed and therefore completely misconstrued. An approach that my father took quite regularly whenever a topic came up that he was uncomfortable with. A few days after her operation, I went to visit her again with my mother and father. This time she was on the seventh floor of the new tower block at Kirkcaldy’s Victoria Hospital, which seemed quite a contrast from the wartime buildings at the Bridge of Earn where she was four years previously. I can recall spending most of the visiting time looking out of the window with its panoramic views over the town rather than speaking with my grandmother, but then what thirteen-year-old boy would do otherwise? Besides, she looked in great health and not unwell in the slightest, sitting up in bed and castigating my mother for making a fuss of her. I cannot say I had any worries for her.

There were a number of follow-up appointments at the hospital; check-ups every now and then, but she made a remarkably quick recovery and by the time the following Easter arrived, she was back on the bowling green and as bright and enthusiastic as ever. There wasn’t anything to warrant any concern as far as I knew. In the years following her hysterectomy she attended the outpatient department at the hospital perhaps once or twice a year. Occasionally, I would accompany her, taking the bus down from Lochgelly through Cardenden to arrive at the hospital forty minutes later for the appointment with the doctor. She was always the epitome of great health, always smiling and always unfailingly respectful and grateful with every doctor that she consulted. And they were always content with her, with good reason, as her progress back to full health was excellent and there didn’t appear to be any recurrence of whatever ‘trouble’ she had that required the operation in the first place. On each visit to the hospital she saw a different doctor, whoever was on rotation at the time in the out-patient department she attended, but the result was always the same – “very happy with your progress and we’ll check you again in six or twelve moths time” – and off she would go until the next visit.

Eleven years pass and the operation was a distant memory. I had left school then taken a year out before starting Podiatry College in Edinburgh, graduating in 1983. My first post was based at the same Victoria Hospital in Kirkcaldy where my grandmother had undergone her hysterectomy and where she still visited very occasionally for her ‘check-up’. She was sixty-seven years old now but still full of the energy and vitality she always exhibited – and still winning competitions at the bowling green. Life was good.

Shortly after I started to work in the September I took her down one evening and showed her my new surgery in a wing of the hospital that had been recently built. The Whyteman’s Brae complex consisted of five specialist wards for psychiatric, psychogeriatric and geriatric patients and several clinics for physiotherapy, podiatry and the other professions allied to medicine that were applicable in such a unit, such as speech and language and occupational therapy. I had been very fortunate as my surgery was pristine and fitted out with the latest equipment and I remember the look of pride not to say amazement when my grandmother walked through the door.

“You’re in a lovely place” she remarked “and if you can look after your patients they way I’ve been looked after here, then you will do very well indeed.” Six months later she started to feel “off colour” and by the time the bowling season resumed that Easter she barely had the energy to play the opening tie. But there was other trouble on the horizon. A week or so before the Bowling Green opened the National Union of Mineworkers called a National Strike and the miners’ walked out of the pits and collieries in protest at the proposed closure program by the NCB under Ian MacGregor. My grandfather, had been retired for five years, but had been through the previous National Strike in 1974, which had been quite traumatic. He was, strictly speaking, not a miner but a blacksmith on the surface and responsible for, amongst other things, the heavy steel cables that raised and lowered the pit cages down the shaft and as such he was permitted to undertake essential maintenance work by the Union, but it was not a comfortable situation for him crossing the picket line every day, albeit with his fellow miners grudging consent. If they were fighting for their jobs, some would have to ensure they had a safe pit to return. Ten years later, these bitter memories were reignited against a different background.

A few days after the bowling season started properly in early May, Agnes visited her GP as she was becoming increasingly tired and exhausted by the slightest effort. A blood test was done and a few days later she was in another hospital for a transfusion. Milesmark Hospital in Dunfermline had a couple of medical wards similar to the geriatric unit at Whytemans Brae and it was here she had her first units of blood. I was unaware of these events at the time and only discovered she had been in hospital a few weeks after the transfusion after I returned from a holiday in Ireland. “It was nothing to worry about”, she said, dismissing my questions. “Just needed a little top-up”.

I don’t know if she knew what was really wrong or whether a diagnosis had been made at that stage, but should that have been the case, it would have been so characteristic of her to play things down. I don’t recall hearing any complaints about her health, ever. Even over the coming months.

During the summer of 1984 and again with a backdrop of a National Strike, Agnes was in Milesmark another three times for more blood; the tiredness and exhaustion returning increasingly and more obvious as the weeks passed. More worryingly, just before her final admission, she began to bruise quite readily and in addition, there were several areas of what looked like pin-prick sized spots on her arms and legs. I had assumed, until then, that her malaise was simply because she was anaemic, but I was wrong. The day after she was admitted at the beginning of October, my father telephoned to say that the consultant had requested a meeting with my mother, aunt and grandfather and the news was not good. She had developed acute myeloid leukaemia and it was unlikely that she would make a recovery this time. By the time I reached the hospital that evening she was already heavily sedated and barely able to speak, but still managed to smile. The following morning she slipped into a deep sleep and four days later, she died.

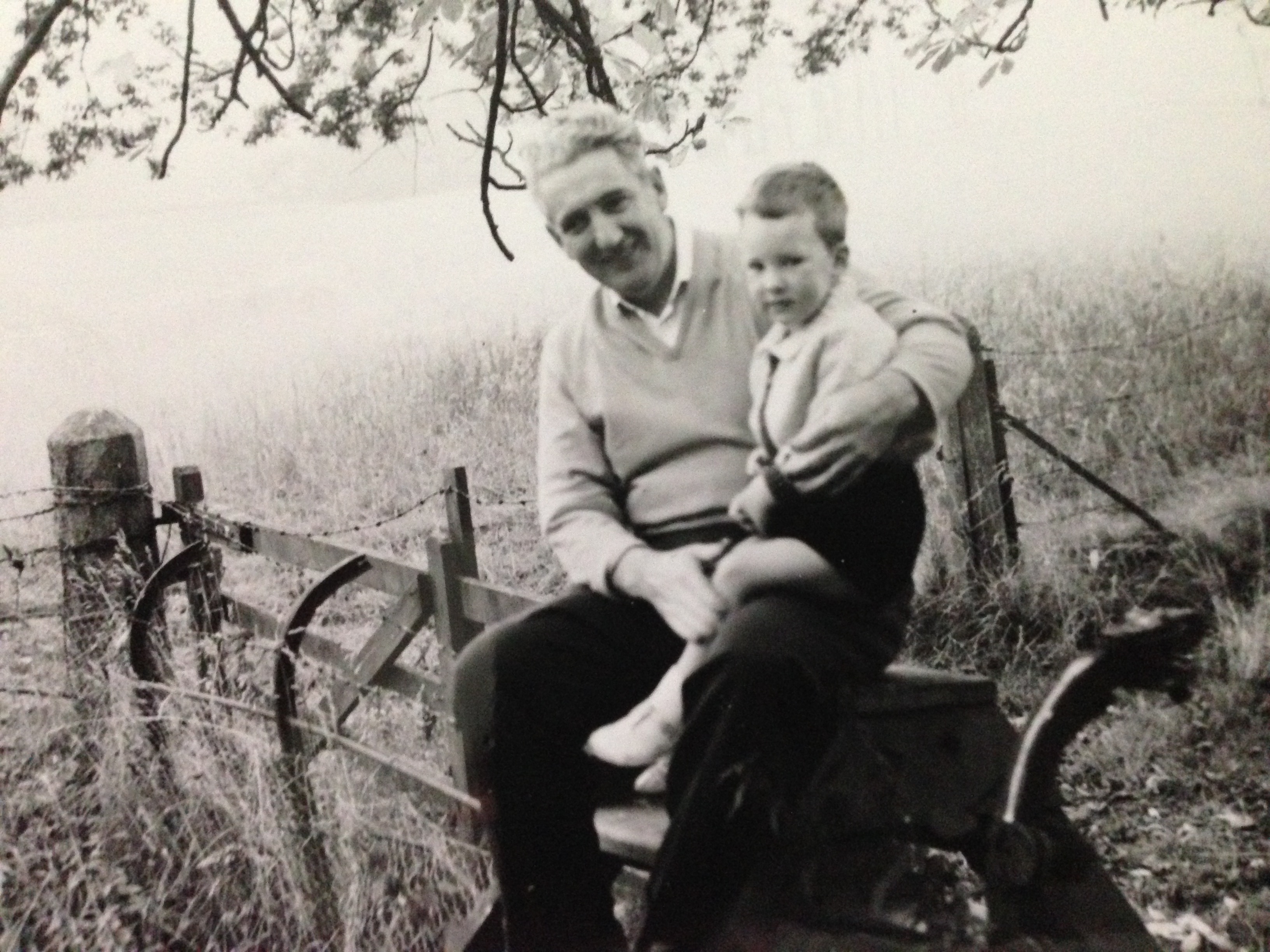

It was the first close relative to me that had died. Both my maternal grandparents were a huge influence in my life, but my grandmother – or Nana – especially. They lived in Gordon Street a hundred yards from our house and I spent much of my childhood with them. I was the eldest grandchild; my sister four years later then our cousin two years after her. My grandfather, being an engineer and blacksmith, had a fabulous wooden garage he built himself, stuffed full of every imaginable tool and implement for all sorts of jobs; a workbench made from railway sleepers and shelves overflowing with jam jars full of screws, nails and three-in-one oil in copper pourers. I used to stay over most Friday nights and on the Saturday morning I helped wash and polish his car – an Austin 1300 – before we started on a job in this magic den of his. He made me my first ice axe from a miners pick welded on to a tubular metal shaft with a bicycle-handle grip to protect bare skin. He was a short, stocky man with a head of bright, thick, white hair lightly bisected with a nicotine-orange streak in his later years. I can still see him standing at his bench in dungarees – an Embassy Red with two inches of quivering, curving ash hanging impossibly above the heavy vice before him. He managed a full cigarette once, the whole ashy length hanging in flaccid surrender whilst he planed some wood. I doubt he even noticed. He was everything you imagine a miner would be; tough as nails, strong as an ox with a dour Fife personality through and through. There is a photograph of the two of us at the stile in the path above the east sands in St Andrews when I was three years old. It provokes both morbid and sobering thoughts when you realise that after the passage of half a century, you have become the same age as your grandparents in faded family photographs.

But if my grandfather gave me my love of taking things apart and finding out how they worked – a practical influence – it was my grandmother’s inspiration in so many other ways that I still treasure to this day. She was a calm, sagacious woman and although she only travelled out of Scotland on a handful of occasions and never further than York or Blackpool, her outlook was anything but parochial. She was the one person I could tell anything to; an absolute confidante and on the one occasion I did run away from home aged eight (my father first giving me a hand to pack my suitcase) I made it no further than her back door. As I write this, it is thirty years since she died and there is rarely a day that I don’t still think of her, but at the time of her death I felt strangely unemotional and disconnected. Perhaps it was the relative suddenness of it all – I had just a few days to prepare for the inevitability yet it still didn’t seem to sink in even on the day she died. It was a surreal feeling and not uncommon, as I discovered subsequently with surviving relatives who experience sudden death of a loved one. In the blink of an eye she was gone and you are thrown into the aftermath of things to organize and people to call so that the time to allow grief to have the time to form properly is deferred. That is how it seemed in hindsight, but at the time it was as though I had become a spectator in a drama witnessing the incomprehension of my grandfather to the inconsolability of my mother and aunt and realizing immediately that the guiding insipration that was needed at this time was not there anymore.

Four months later, on a Friday afternoon, I had an out-patient clinic running at Whyteman’s Brae in Kirkcaldy when I noticed my penultimate patient of the afternoon had the same name as my grandmother, however her address was in one of the small fishing villages in the Neuk of Fife. But when I collected the patient notes from the front office, I discovered that the records office had sent the wrong notes and had inadvertently sent those of my grandmother instead. Thirty-years ago it took some months to close patient records, especially where care was spread over different hospitals and all the correspondence and ward notes were gathered and filed manually – and it wasn’t uncommon to receive a number of wrong records in any clinic, but it still came as something of a shock when I noticed the address on the front label. I took it back to my room with the rest of the bundle and sat down and began to read.

The first set of notes were from the Bridge of Earn Hospital about her foot surgery fourteen years earlier including the referral letter from her General Practitioner in Lochgelly, Dr Roy Blues, his illegible handwriting immediately recognisable. I could just make out ‘bunion’ and the name of the surgeon, but that was about it. The surgical and nursing notes followed, then the paperwork changed to the Victoria Hospital and her operation for her ‘woman’s troubles’ – the ovarian cancer. This was my first surprise. Even after the passing of the years and her death, I still hadn’t known that her hysterectomy had been performed for underlying pathology so the notes from her gynecologist, Dr Hill were a revelation of sorts. There was a letter to Dr Blues shortly after her hysterectomy informing him that the operation was a success and that she would be put on a maintenance regime of cyclophosphamide and reviewed in six and twelve months time. This was followed by a series of out-patient records that coincided with her annual or bi-annual check-ups before the final tranche of records from Milesmark leading up to her death. But it was the final piece of correspondence that really stopped me in my tracks. It was a letter from a Consultant Haematologist to the doctor in charge of her care at Milesmark during her final weeks. It was a single piece of A5 white hospital notepaper, neatly typed with two short paragraphs; the first, thanking the doctor for asking him to review my grandmother’s case and the second, informed him that she had “developed acute myeloid leukaemia which will be refractory due to the prolonged exposure to cyclophosphamide.”

I hadn’t heard the term ‘refractory’ before, but could easily make an informed guess as to what it meant, given the eventual outcome. Nor had I heard of cyclophosphamide and why she was on such a regime in the first place. There was no internet and no quick answers then, so it had to wait until the end of the clinic and a visit over the road to the hospital library before I found what I was looking for.

Cyclophosphamide is a drug that was commonly used as an adjunct therapy in the treatment of some cancers, including ovarian tumours. One of its actions is as a bone marrow suppressant in particular to the formation of T lymphocytes, a form of white blood cell that are thought to increase the risk of further cancer developing. The literature went on to state:

“Cyclophosphamide is used for the treatment of numerous malignant processes and certain autoimmune diseases. Goals of therapy are prompt control of the underlying pathological process and discontinuation or replacement of cyclophosphamide with less toxic, alternative medication as soon as possible in order to minimize associated morbidity. Regular and frequent laboratory evaluations are required to monitor renal function, avoid drug-induced bladder complications, and screen for bone marrow toxicity. Cyclophosphamide has severe and life-threatening adverse effects, including acute myeloid leukemia, bladder cancer, hemorrhagic cystitis, and permanent infertility, especially at higher doses.”

I re-read her notes again and couldn’t locate a specific entry for the proposed length of the course she had been recommended after her hysterectomy. The letter from her gynaecologist to Dr Blues was the only mention of the drug and that she was due to be reviewed in six and twelve months time, but that was it. Even on her subsequent out-patient reviews there was never mention of the drug again – most of the entries simply noting that she looked fine and had no problems before suggesting a review at some future point, usually twelve or eighteen months time. I then read through her later notes from Milesmark and found a hand-written entry from her first visit the previous year when she received her initial transfusion, made by a ward doctor following a telephone call with the haematologist. Underlined, it read simply, “discontinue cyclophosphamide immediately”. At the time she had been on the drug continuously for eleven years, but I couldn’t find any information regarding recommended treatment courses so I had no way of determining if this was normal or otherwise, but the ‘prolonged exposure’ was sitting uncomfortably in the back of my mind by that stage and I had an inkling that something was not quite right.

I took her records home with me that evening, in contravention of hospital policy, of course, but I needed to find out whether anyone else I the family was aware of this. They weren’t; at least according to my father. Nor did he know anything about cyclophosphamide or its ability to cause AML or what her recommended course was. Rather he was dismissive. “What do you want to know that for?” he asked, with not a little menace in his voice.

It is worth remembering that the issue of medical malpractice was very much under the radar until a relatively short time ago. In the early 1980s, it was generally accepted that mistakes could sometimes happen, but the apportionment of blame and liability for such a concept was entirely foreign in the National Health Service. I have heard my grandmother say on many a time that accidents occur for any number of reasons but providing there was no intent to harm, there should be no blame or recriminations (most usually when waiting for a confession and explanation of any number of misdemeanors by myself) – and so it seemed a likewise philosophy was similarly adopted by my father as he contemplated what to say. He was by then, a district chiropodist, employed by the same NHS Board in Fife as I was and any thought about raising any concern over an incident like this would not have even entered his head. The Health Service was very much regarded as a big family; a close knit organization with a proud tradition in Scotland but with a definite hierarchical structure and it would, with hindsight, have been a formidable prospect for someone even in his position to challenge established medical practice, especially over something he would have little, if any, authoritative knowledge about. “How do you know she was on it for too long?” he asked. And of course, he was right. I didn’t know that for certain. Perhaps she needed to be on a maintenance regime of the drug for that eleven years and it was just an unfortunate consequence that she went on to develop AML, but it was the prolonged exposure that still sat firmly in my thoughts later that night as I pondered what to do.

On the Monday morning I looked through the hospital directory until I found the number for the Consultant Haematologist, Dr John MacCallum, whose office was located in the main hospital block. I wasn’t at all sure what I would say to him or what his reaction might be. I was twenty-three years old and only been graduated for around eighteen months and I remember being extremely nervous when I eventually dialed his extension. His secretary answered and I asked her if it would be possible to see him about a patient later that day. She suggested after his ward round at 11.30am.

Dr MacCallum was a quietly spoken and extremely courteous man who had taken up his consultant’s post a year earlier and welcomed me into his office with typical grace. “How can I help you?” he asked. My hands were shaking as I passed him my grandmother’s records and opened them at his letter.

“I was wondering if you could tell me what this means?” I said, pointing to his second paragraph. He read the letter then looked back at the previous pages then said, “This patient died last year. What is your interest in this exactly?”

“She was my grandmother.” I went on to explain the circumstances of my discovery, courtesy of the patient record department.

“I see.” He said, before he filled in the gaps. He informed me that he had asked to review my grandmother’s records the previous year, shortly after she had her first blood test in the weeks after the opening of the Bowling Green when she started to feel unwell. Her blood test showed abnormally low numbers of both platelets and white blood cells and he had flagged the result up for further clinical investigation. The transfusion she had was not for haemoglobin for anaemia as I suspected, but for platelets. She had a bone marrow aspiration carried out, which again I knew nothing about at the time, and this fuelled his suspicions that she was starting to develop a form of leukaemia. It was at that point he recommended discontinuing the cyclophosphamide. Later, when she began to exhibit the bruising and the pin-prick haemorrhages on her arms and torso, which he called thrombocytopenia, he made the final diagnosis of AML.

“How long should she have been on it?” I asked, acutely aware I was on difficult ground.

“I would think between six and eighteen months.” He replied. “But that would depend on the diagnosis at the time. I’m not sure what happened here with your grandmother, it was possibly an oversight or a mix-up with her prescription, but she had been exposed to this for quite some time and that wouldn’t have helped.”

I tried to take in what he was saying and thinking how to reply when he said; “I’m sorry you had to find out like that and I’m really sorry for your loss.” And I could tell that he was genuine with it. He handed me back the notes and suggested I return them to the medical record department and that was that. I didn’t find out any more. There was no investigation to determine who knew what or why. I’ve no idea if my grandmother was even aware that it had been the chemotherapeutic drug she had been prescribed all those years that was the likely cause of her death. She may have been informed, I forgot to ask, but if she had, it was probable that she would have kept the information to herself anyway, that being the measure of the woman she was. She certainly wouldn’t countenance a fuss.

Trying to determine what might have happened is simply conjecture. The failure, if that is the correct term, could have been in several areas. There was no computerisation then and medical notes were anything but contemporaneous and standard clinical practice was more of a verbal art form handed down from senior consultants to their protégées than in published guidelines and protocols. Certainly someone should have realised that she had been taking the drug for much longer than usual, but who and when? The environment wouldn’t have helped; the continual merry-go-round of registrars, house officers and trainee doctors through the various specialisms in the hospital set-up provides an obvious impediment to continuity of care where records may not be as detailed as they could be. There was no forward review of her medication written up in the notes for guidance in future consultations, just a record of how she presented and how she felt. It was, in all probability, a simple administrative error; an oversight, as the consultant had suggested; an unfortunate error but one with significant and avoidable consequences.

I returned her notes to the records department later that day and filed the slip with the other Agnes MacDonald’s podiatry treatment from before the weekend in the correct patient file. That was the end of the matter. There was nothing else I could have done and even if there was I don’t know if I had the capacity to take it any further and whether it would have done any good. The philosophy was different then and it was generally accepted that the Health Service, as with most of the institutions of the State always acted in the best interests of the individual and where the outcome was not as expected and someone went on to suffer loss, injury or life, it was seen, from my perspective at the time as a tragic mistake; something to acknowledge and learn from rather than apportion blame or liability. Hospital management was simply administrative and supported clinical practice whose principal oversight was through the various consultant committees. However, changes were on the horizon with the recent publication of Roy Griffith’s report on general management in the NHS but his recommendations would take time to filter through, but even then it is doubtful if they would identify simple failings of the kind that compromised my grandmother’s care.

I am being careful with my words as I do not seek to apportion any blame; I do not find the concept helpful in the slightest as we understand in its current lexicon and I think I still share my grandmother’s philosophy too in that providing there is no intent to harm there should be understanding and a learning rather than retribution and punishment, but I am only too well aware such a view is not in fashion much these days. The pendulum has very much swung in the other direction since my grandmother’s death and after the likes of Shipman, Alder-Hey and the countless other ‘scandals’ in our State Health Service, there is an entire industry devoted to medical malpractice with enormous attendant costs. Countless Public Inquiries with armies of barristers, solicitors and traumatised relatives pouring over endless evidence of failings in care has achieved little more than promoting a defensive culture riven with fear and intimidation, not least because of the enormous liabilities the NHS is accruing from an equally expanding battery of claimants. Such are the times we are in, but it would have seemed absurd, even wrong to seek financial compensation or bring someone to task for a simple oversight that had inadvertently contributed to someone like my grandmother’s death, even though such an approach would not be out of the norm today and probably even encouraged. Especially by the industry geared up to profit the most out of it – our legal profession and in particular those concerned with regulation and compliance.

Thirty years ago I was a new entrant into our National Health Service – a lowly foot soldier, as it were, but nonetheless very enthusiastic about my profession and its prospects. It seemed a time of great promise and hope as I was instilled into a great institution founded on tremendous principles – and there was another more personal connection closer to home. The wife of Aneurin Bevan, the architect of the NHS, was Jennie Lee, later Baroness Lee of Asheridge, was born in Lochgelly and very much one of my grandfather’s favourite people and the subject of many a tale. She was ten years his senior and he could well remember her firebrand style supporting the miners through their various struggles in the years before she became a prominent Member of Parliament in her own right. The prospect of a career in the Health Service was something really I looked forward to. It seemed worthwhile and exciting. It was also set in a time of great innocence and naivety, for me at least. But the coming years were about to change all that.

It would take decades and a completely different set of circumstances before my views about ‘great’ institutions of State and their responsibilities and functions were challenged again and another two decades after that before that any lingering confidence in them finally dispelled.